Additional information

| Cover | Paperback |

|---|---|

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 2005 |

| Includes | Manual and CD |

| Requirements |

$44.00

| Cover | Paperback |

|---|---|

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 2005 |

| Includes | Manual and CD |

| Requirements |

Overview

The LEARN Strategy is used by cooperative groups to learn information together. This professional development program was designed to provide instruction to teachers so that they can teach the LEARN Strategy to their students. This research study was conducted in 16 fifth-grade general education classes. Five teachers participated in this CD program (hereafter referred to as the “multimedia workshop”) to learn how to provide instruction in the LEARN Strategy. They taught a total of 92 students the strategy. Six additional teachers simply read the instructor’s manual for the LEARN Strategy and taught the strategy to their 120 students. Five additional teachers and their 81 students served as comparison classes. The comparison teachers did not teach the LEARN Strategy to their students and did not receive any instruction related to the LEARN Strategy. The teachers were randomly assigned to the groups.

Results

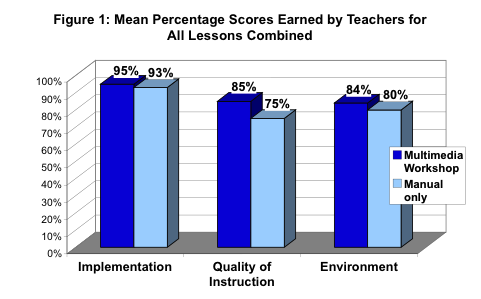

Measures were gathered on the fidelity of the multimedia workshop teachers’ and manual-only teachers’ implementation of the instruction, their quality of instruction, and the quality of the instructional environment. The results are shown in Figure 1. No differences were found between the results for the two groups of teachers who received instruction.

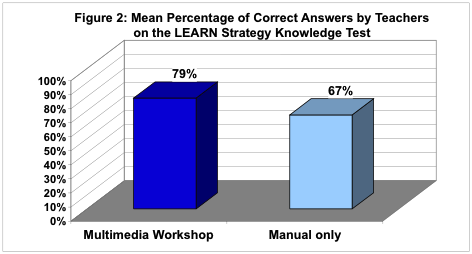

Figure 2 displays the mean percentage scores the two multimedia-workshop and manual-only teachers earned on a test of their knowledge of the instructional methods and the LEARN Strategy. No difference was found between the test scores for the two groups, F(1,9)=1.07, p = .328.

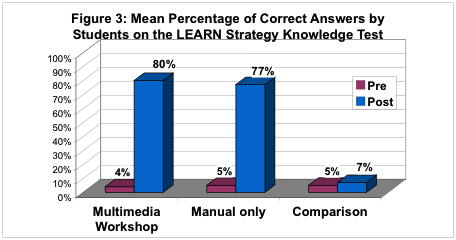

Figure 3 displays the mean percentage scores earned by students of the three groups of teachers on a written test of their knowledge of the strategy. The data were analyzed comparing the three groups of students’ raw posttest scores while controlling for the pretest scores. The results showed that the adjusted mean scores on the posttests were significantly different, F(2,13)=52.7, p = .0001. Follow-up comparison tests revealed significant differences between the posttest scores earned by the comparison and the multimedia-workshop groups, t(1, 13.3)=9.01, p < .0001, and between the comparison and the manual-only groups, t(1, 13)=8.99, p < .0001. The posttest scores of the multimedia- workshop group and the manual-only group were not statistically different from each other.

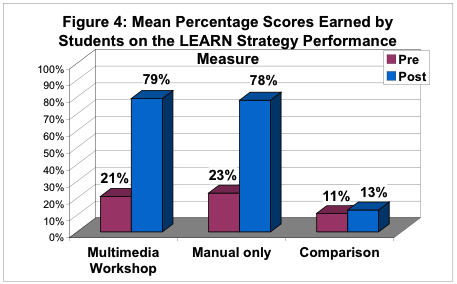

Figure 4 displays the mean percentage of points earned by the students as they used the LEARN Strategy in cooperative groups in their classrooms to study information together. These performance data were analyzed comparing the three groups of students’ posttest raw scores while controlling for the pretest scores. The results showed that the adjusted mean scores on the posttests were significantly different, F(2,12.2)=33.21, p<.0001. Follow-up comparison tests revealed significant differences between the posttest scores of the comparison and the multimedia-workshop groups, t(1,12.2)=6.97, p<.0001, and of the comparison and the manual-only groups, t(1,12.3)=7.26, p<.0001. The posttest scores of the multimedia-workshop group and the manual-only group were not statistically different from each other.

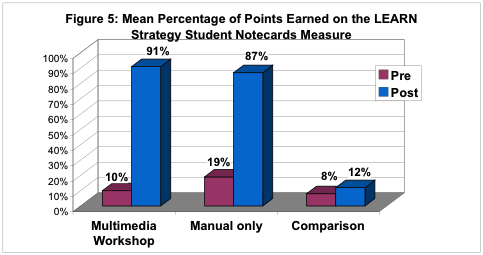

Figure 5 displays the mean percentage of points earned by the students on the study notecards they created in their cooperative groups. The notecard data were analyzed comparing the three groups of students’ posttest raw scores while controlling for the pretest scores. The results showed that the adjusted mean scores on the posttests were significantly different, F(2,13.1) = 37.34, p < .0001. Follow-up comparison tests revealed significant differences between the posttest scores of the comparison and the multimedia- workshop groups, t(1, 13) = 7.71, p < .0001, and between the comparison and the manual-only groups, t(1, 13.3) = 7.37, p < .0001. The posttest scores of the multimedia- workshop group and the manual-only group were not statistically different from each other.

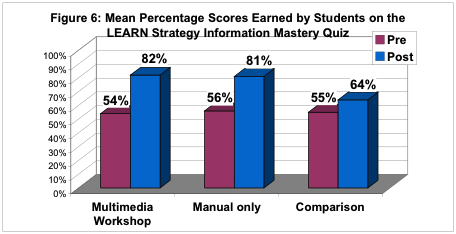

Figure 6 displays the mean percentage scores earned by the students after they were asked to study the information in a short reading passage in their cooperative groups and then take a test over the information independently. The Information Mastery Quiz data were analyzed comparing the three groups of students’ posttest raw scores while controlling for the pretest scores. The results showed that the adjusted mean scores on the posttests were significantly different, F(2,12.2) = 15.34, p = .0005. Follow-up comparison tests revealed significant differences between the posttest scores of the comparison and the multimedia-workshop groups, t(1, 12.6) = 5.03, p = .0003, and of the comparison and the manual-only groups, t(1, 12.2) = 4.69, p = .0005. The posttest scores of the multimedia-workshop group and the manual-only group were not statistically different.

Conclusions

These results show that the Professional Development CD Program is effective in instructing teachers in how to teach the LEARN Strategy to students. There were no significant differences between multimedia-workshop groups and manual-only groups of teachers and students, and both groups of experimental students performed significantly and substantially better than the comparison students on all three student measures. Thus, the professional development CD program for teachers associated with the LEARN Strategy is effective in producing student change.

Reference

Vernon, D.S. (2003). Effects of a professional development software program for the LEARN Strategy Program: Progress Report. SBIR Phase II #R44HD36139. Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

D. Sue Vernon, Ph.D.

Affliations

My Background and Interests

By wearing my different hats (a university instructor, a certified teaching-parent, a trainer and evaluator of child-care workers, a SIM professional development specialist, a parent of three children (one with exceptionalities), and a researcher), I have gained knowledge and experience from a number of perspectives. I have a history of working with at-risk youth with and without exceptionalities (e.g., students with learning disabilities, emotional disturbance, behavioral disorders) in community-based residential group-home treatment programs and in schools. I also have extensive experience with training, evaluating, and monitoring staff who work with these populations, and I have conducted research with and adapted curricula for high-poverty populations. In addition to the LEARN Strategy program and other Cooperative Thinking Strategies programs, I’ve developed and field-tested interactive multimedia social skills curricula, community-building curricula, communication skills instruction, and professional development programs. I have also developed and validated social skills measurement instruments. As a lecturer of graduate-level university courses in the Department of Special Education at the University of Kansas, I have taught courses designed to enable teachers to access and become proficient in validated research-based practices.

The Story Behind the LEARN Strategy Professional Development CD

My focus for the last 30 years has been on helping youths learn, and especially on helping them learn how to use social skills. My interest in social skills instruction began when I was a teaching-parent in a group home for adolescents who had a history of social problems. Clearly, those youths had not learned the social skills they needed to be successful in today’s world. Nevertheless, experience showed they could learn to use social skills well, given the right type of instruction. Later, I was the co-founder and Director of Training and Evaluation of the Teaching-Family Homes of Upper Michigan, originally developed through funding from the Michigan State Department of Mental Health and Father Flanagan’s Boys Home. This new agency eventually provided services to over 1,000 youths per day in schools, residential group homes, regional treatment centers, treatment foster homes, schools, and in counseling centers. My primary responsibility in this position was teaching adults (e.g., parents, teachers, foster parents, counselors) to teach social skills to children, and everyday I witnessed these adults successfully teaching the various skills to the youths in their care. Unfortunately, the population receiving instruction was often children who were already involved in the juvenile justice “system.” They were in trouble and had been removed from their homes. As I watched their growing success, I wanted to find a way to introduce social skills instruction as a way to preventsocial problems – I wanted to teach children alternative ways of behaving that would help them not only to stay out of trouble but also to create and maintain relationships. I thought the perfect place to prevent problems would be in the general education classroom beginning in elementary school.

As a result, a whole line of research on social skills instruction was born. During early research efforts, I began observing and recording social interactions as students worked in cooperative groups on different types of tasks (and I was appalled at how the students treated one another – especially how other students treated students with exceptionalities). I surveyed teachers and found that they actively supported social skills instruction and were looking for ways to enhance productivity in cooperative groups. They had specific types of tasks in mind that they wanted their students to accomplish. For example, in addition to basic interaction skills, they wanted their students to learn how to study together and tutor one another. Thus, my colleagues and I developed and tested the LEARN Strategy program in general education classrooms. Our goal for the Cooperative Thinking Strategy Series was to develop programs that could be used in general education classes and that would benefit students with and without exceptionalities. We wanted students to learn ways to cooperate with each other that they could use in their future lives, such as in post-secondary schools, work, and community situations. Once the LEARN Strategy Program was developed and shown to be effective, we wanted to provide an inexpensive way for teachers to learn how to teach the LEARN Strategy. Thus, the LEARN Strategy Professional Development CD was born. It contains step-by-step instructions on how to teach the LEARN Strategy along with videoclips of a teacher teaching the strategy.

My Thoughts about LEARN Strategy Instruction

I have observed the LEARN Strategy program being successfully used in schools and in group-home settings with elementary and middle-school students and believe the program can be easily adapted for use in other settings especially with high school and college students where students are required to memorize large amounts of information. This was an especially fun strategy to observe students using because the student teams developed such creative memory devices. In one class, I observed the students learning what states were in each region in the U.S., the capitals of all 50 states, resources within the states, and so on. In one activity, teams were assigned regions and were asked to use the LEARN Strategy to create a memory device for remembering the states within their region. Once they became experts on their region, all of the teams split up and took turns teaching their memory device to other teams. The activity was a success. The teacher told me it was the first time in 20 years of teaching that 100% of her students received a perfect 100% score on the test covering the states and regions. She also mentioned that she surveyed her students each year about their experience in fourth grade. On the question asking what was their favorite part of fourth grade, five or six students answered “learning the LEARN Strategy.”

In teaching my university classes after I’ve introduced and taught my students how to teach the SCORE Skills and LEARN Strategy to their students, I give four-person teams a page of information that I have collected from Science and History textbooks related to a variety of topics. I ask them to practice using the LEARN Strategy to organize the information and create memory devices. Through the years, my graduate students have created especially entertaining memory devices! Almost all my university students comment that not only will they teach their students how to use the LEARN Strategy, but they will use it individually and with study partners as they complete their advanced degrees.

Teacher and Student Feedback on the LEARN Strategy

Comments from teachers about what they have liked most about the program include “The LEARN Strategy addresses a very weak area in our curriculum and has great potential for empowering students to learn more successfully”; “I am thrilled that I have another way to help my students succeed”; “It was so useful, the kids really liked using it, and they had fun.” Student comments related to the LEARN Strategy included, “I have a better memory now,” “It gave me a B+ in social studies,” “It helped me do reports and homework better,” “It helps you remember things when you study,” and “It helped me study for tests and understand things easier.”

My Contact Information

Please contact me at svernon2@windstream.net

LEARN Strategy: Instructor’s Manual

LEARN Strategy: Instructor’s Manual