Additional information

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 193 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 2008 |

| Requirements |

What’s in a word, anyway? Well, it turns out that many words have parts, and knowing what those parts mean enables a student to predict the meaning of those words. These parts are based on words in the Greek and Latin languages and can be mixed and matched in many combinations.

The Word Mapping Strategy was specially designed to enable students to identify the parts of unknown words, to identify the meaning of the parts, and to predict the meaning of those unknown words. Such skills are critically important when reading and when taking tests. This instructor’s manual contains four initial lessons for introducing prefixes, suffixes, and root words and the steps of the Word Mapping Strategy. It also includes instructions, learning sheets, and quizzes for teaching the most frequently encountered prefixes, suffixes, and root words. The strategy can be taught in general education and special education settings. Research has shown that students who learn the strategy not only learn the meaning of targeted words, but they learn how to predict the meaning of unknown words.

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 193 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 2008 |

| Requirements |

Overview

The Word Mapping Strategy is a strategy students use to predict the meaning of new words. Thus, the Word Mapping Strategy is a generative strategy in that students can use it to unlock the meaning of many new words within word families. The effects of teaching the Word Mapping Strategy were compared to the effects of teaching the LINCS Vocabulary Strategy, which is a word-specific strategy. That is, the LINCS Strategy is used to memorize the meaning of a word, once that meaning of that word is known. Unlike the Word Mapping Strategy, it was not designed to be used to predict the meanings of words.

The study included a total of 230 ninth graders in nine intact general education English classes. Students with disabilities (SWDs) and without disabilities (NSWDs) were enrolled in all of the classes. Three classes participated in each of three groups: the group receiving instruction in the Word Mapping (WM) Strategy (n= 10 SWDs, 69 NSWDs) , the group receiving instruction in the LINCS (VL) Strategy (n = 6 SWDs, 73 NSWDs), and a comparison (test-only [TO]) group (n = 8 SWDS, 64 NSWDs). Classes were randomly selected into the two experimental groups. The third group of classes served as a normative comparison. Thus, a pretest-posttest control-group design was combined with a pretest-posttest comparison-group design.

Results

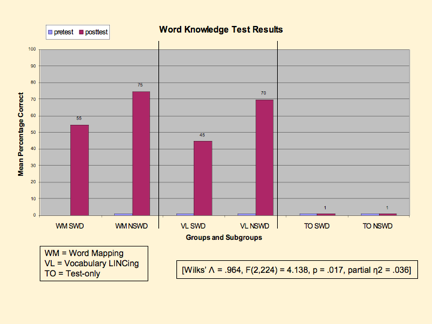

Figure 1 displays the mean percentage of 20 words that students in both experimental groups (i.e., the WM and VL groups) learned during the strategy instruction as determined by a written test that required students to write the meaning of the words. With regard to changes from pretest to posttest, the three-way interaction of time x subgroup x group was found to be significant, Wilks’ Λ = .964, F(2,224) = 4.138, p = .017, partial η2 = .036 (a small effect size). When the file was split on subgroup, the time x group interaction was significant for the SWDs, F(2,21) = 12.90, p < .001, partial η2 = .563 (a large effect size), and for the NSWDs, F(2,203) = 367.388, p < .001, partial η2 = .780 (also a large effect size). The paired-sample t-tests revealed that a significant difference existed between the pretest and posttest scores for the SWDs in the WM group, t(9) = -6.280, p < .001, d = .957, and for the NSWDs in the WM group, t(68) = -29.626, p < .001, d = .138 (both are large effect sizes). No differences were found for the TO subgroups.

No differences were found between the posttest scores of the WM and VL groups on this measure. That is, both groups learned the vocabulary words they were taught equally well. However, large significant differences were found between the posttest scores of the WM subgroups and the TO subgroups [SWDS: F(1,21) = 24.056, p < .001, partial η2 = .546 (a large effect size) ; NSWDs: F(1,202) = 574.539, p < .001, partial η2 = .740 (a large effect size)].

Figure 1: Mean percentage of words for which students wrote the meaning

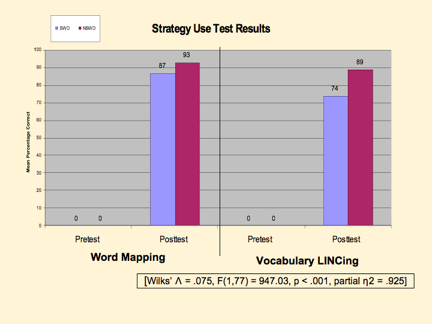

Figure 2 displays the mean percentage of points students earned on a test of strategy use. Students in the WM group took a test requiring use of the Word Mapping Strategy; students in the VL group took a test requiring use of the LINCS Vocabulary Strategy. With regard to the WM group, a statistically significant difference was found between students’ pretest and posttest scores. Wilks’ Λ = .075, F(1,77) = 947.03, p < .001, partial η2 = .925 (a large effect size). There were no differences between the SWDs and the NSWDs in learning the Word Mapping Strategy.

Figure 2: Percentage of points earned on a test requiring use of the strategy

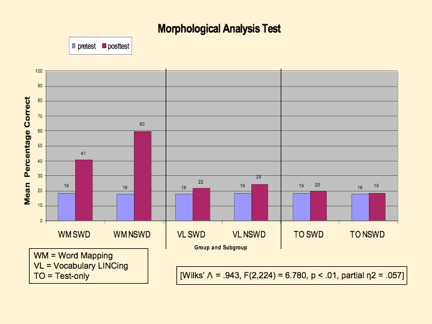

Figure 3 displays the percentage of points earned by the students in all three groups on a written test that required them to predict the meaning of new words. With regard to changes between pretest and posttest scores, the three-way interaction of time (pretest to posttest) x subgroup (SWD and NSWD) x group (WM, VL, and TO) was significant, Wilks’ Λ = .943, F(2,224) = 6.780, p < .01, partial η2 = .057 (a medium effect size). When the file was split by subgroup, the time x group interaction was significant for the SWD subgroup, Wilks’ Λ = .613, F(2,21) = 6.630, p < .01, partial η2 = .387 (a large effect size), and for the NSWD subgroup, Wilks’ Λ = .287, F(2,203) = 251.790, p < .001, partial η2 = .713 (a large effect size). Paired-sample t-tests revealed a significant difference between the pretest and posttest scores for the SWDs in the WM group, t(9) = -3.45, p < .01, d = .896 (a large effect size), and for the NSWDs in the WM group, t(68) = -21.256, p < .001, d =.129. The posttest scores were significantly higher than pretest scores in each case. No significant differences were revealed for the subgroups within the VL and TO groups.

With regard to the differences between the posttest scores of the three groups on this prediction test when the pretest scores served as the covariate, the two-way interaction of strategy group and disability subgroup was significant, F(2,223) = 6.61, p = .002, partial η2 = .06 (a medium effect size). When the file was split on subgroup, the main effect of strategy group for the SWDs was significant, F(2,203) = 250.51, p < .001, partial η2= .713 (a large effect size).

Figure 3: Percentage of points earned on a test requiring the prediction of word meanings

Pairwise comparisons revealed that there was a significant difference between the posttest scores of the SWDs in the WM group versus SWDs in the VL group, F(1,20) = 8.599, p < .01, partial η2 = .301 (a large effect size), and versus SWDs in the TO group, F(1,20) = 11.801, p< .01, partial η2 = .371 (a large effect size). Mean posttest scores for the WM SWD group were significantly higher than the mean posttest scores for the VL and TO SWD subgroups. A significant difference was found between the NSWDs in the WM group versus NSWDs in the VL group, F(1,202) = 344.281, p < .001, partial η2 = .630, and versus NSWDs in the TO group, F(1,202) =404.275, p < .001, partial η2 = .667. Again, the WM NSWDs’ mean scores were significantly higher than the mean scores for the VL and the TO NSWD groups, and the effect sizes were large.

Conclusions

Students in general education classes were able to learn the Word Mapping Strategy and the meaning of words taught during Word Mapping instruction. The effect sizes in each case were large. In addition, their learning of the strategy enabled them to predict the meaning of significantly more words after instruction than before instruction. Additionally, their scores on predicting the meaning of words were significantly higher than the scores of the other groups at the end of the study. There were no differences between the performance of students with and without disabilities.

Reference for this study*

Harris, M. L., Schumaker, J. B., & Deshler, D. D. (in preparation). The effects of strategic morphological analysis instruction on the vocabulary performance of secondary students with and without disabilities. (Available through Edge Enterprises, Inc. or call Edge for updated publication information.)

*This research study won the Researcher of the Year Award from the Council for Learning Disabilities in 2008.

Monica L. Harris

Affliations

My Background and Interests

In the mid-1990s, I started my graduate program in special education at Eastern Michigan University. Here, I learned about the SIM strategies from Kansas and with the encouragement of a professor (and mentor), Dr. Larry Bemish, I made the yearly pilgrimage to Lawrence, Kansas to “get trained” and learn about research-based instructional strategies. That’s all it took – I was hooked (and a SIM lifer)! Currently, my research interests include response to intervention, adolescent literacy, and teacher preparation.

The Story Behind this Product

My first teaching position was as an eighth-grade social studies teacher in a building where the staff embraced the middle-school philosophy of “teaming” and implemented the concept of full inclusion. My “team” was comprised of science, math, and ELA teachers, and I was the social studies teacher. As a team, we embraced the idea that all kids can learn, and our administration was very supportive and encouraged us to try new and different things. The students whom our team served were academically diverse (i.e., accelerated/gifted, special education, at-risk, etc.) and came from low SES families; a high percentage of them received free/reduced-price lunches. In order to meet the various learning styles and needs of our students, I had to think strategically about how I could truly differentiate my instruction and raise student performance.

As part of our teaching responsibilities, we taught an “academic enrichment” (AE) course as our elective course. Academic enrichment could emphasize any subject as long as it increased the academic performance of students in a specific content area. Most teachers chose to drill deeper into the content area they currently taught. For example, a science teacher might choose to teach a unit on the “wetlands” or an ELA teacher might spend a 15-week semester on poetry. I chose to teach a study-skills course. The students who enrolled in the course were at-risk, received special education programming, or were struggling academically in some way. In this class, I focused on teaching students the skills and meta-cognitive strategies required to be successful in their core courses. To begin, I focused my instruction on vocabulary, realizing the importance of vocabulary knowledge and its pervasiveness across the curriculum. Typically, the very first strategy I taught my students was the LINCS Vocabulary Strategy (Ellis, 1992) – they loved it! I loved it! However, after the “love-fest” was over, the reality of trying to keep up with all of the curriculum terminology and vocabulary lists for each course overwhelmed students (and me!). I wondered how I could help students improve their comprehension of content without insisting that they take the time to memorize every word on the list.

During the summer months, I taught summer school. Teaching summer school provided me with the opportunity to teach new strategies I had learned at KU right away in the classroom. I had my own “lab” (so to speak). One summer in particular, after assessing my students on their present level of basic decoding and reading comprehension skills, I found many (if not all) would greatly benefit from learning the Word Identification Strategy (Lenz, 1990). With great enthusiasm (and naiveté), I jumped in with reckless abandon! After teaching the SCORE Skills (Vernon, Schumaker, & Deshler, 1993) to establish a community of learners and provide students with a way for them to participate effectively in cooperative learning groups, I started the Word Identification Strategy instruction. After getting student buy-in, providing rationales for learning the strategy, and teaching about prefixes and suffixes, students wanted to know about the meanings of these word parts. Evidently, identification wasn’t enough for some of them. I found myself looking for more resources to help students to learn the meaning of each prefix and suffix on the lists associated with the Word Identification Strategy. Eventually, I did what only any good LINCS vocabulary teacher would do, I had them make LINCS cards to learn the meanings of the word parts! Somehow, this was only a start – they needed more. I needed more! However, I wasn’t sure how to approach this. I kept working on the issue, and the rest is history.

My Thoughts About Instruction in the Word Mapping Strategy

Once I was accepted to attend KU as a doctoral student, I looked forward to pursuing a line of research. This is when it all came together! I drew heavily on my prior experiences as a general and special educator. I remembered how critical vocabulary knowledge and learning is to academic achievement and content comprehension in the classroom. I guess my thoughts regarding the strategy are that should be taught in general education classrooms and that educators need to take advantage of teachable moments in content courses to prompt the use of Word Mapping by students. For example, science, math, and history teachers should consider how to embed the use of high-frequency affixes (prefixes and suffixes) and roots in their weekly lessons and/or units. Also, I have found that when teachers share the etymology (word origin) of academic vocabulary with students, this information often creates background knowledge (and, at times, a visual image) that enhances recall and comprehension. What a great way to bring history and the sciences to life!

Teacher or Student Feedback on this Product

Overwhelmingly, teachers share with me success stories about how wonderful Word Mapping is for their students. Often, I hear, “Why wasn’t I taught this in school?” or “Thank goodness I had to learn Latin in school!” As I visit schools and work with content-area teachers, I find they understand the importance of word study (teaching students about word origin and Greek/Latin etymology) and connecting this information to their curriculum. Specifically, secondary teachers teach this strategy to focus student learning on high-frequency prefixes, suffixes, and roots. As one student told me, “Word Mapping helped me to prepare for ACT, and I learned to predict meanings of words I did not know – that was cool!”

My Contact Information

Informing Others Digital Program Flash Drive

Informing Others Digital Program Flash Drive