Additional information

| Publisher | CRL |

|---|---|

| Other Materials Needed | Graded Reading Passages |

| Requirements |

For older students who have trouble reading, school is not just a struggle, it’s a nightmare. How can they DO the reading that’s required? If they can’t pronounce the words in their textbooks, why even try to read a whole chapter?

| Publisher | CRL |

|---|---|

| Other Materials Needed | Graded Reading Passages |

| Requirements |

Study 1

Overview

The Word Identification Strategy is comprised of a set of steps students use to decode multisyllabic words, like the words they find in secondary science and social studies textbooks. Twelve students with LD in grades 7, 8, and 9 participated in this study. At the beginning of the study, their reading scores on a standardized test ranged from the third to seventh grades. The study employed a multiple-baseline across-subjects design. All participants were taught the strategy.

Results

During baseline (before instruction), on a test of oral decoding, the students made as many as 21 errors as they were reading 400-word passages written at their ability level and 37 errors as they were reading passages written at their grade level. After instruction in the strategy, all students reached the mastery requirement of 6 or fewer errors in a 400-word passage within 5 practice trials when reading ability-level passages and within 9 trials when reading grade-level passages. At the end of the study, they made an average of 5 errors as they were reading 400-word passages taken from subject-area textbooks for their grade level.

During baseline, the students’ average comprehension scores were 83% on ability level passages and 39% on grade-level passages. After instruction, their average comprehension scores were 88% on ability level passages and 58% on grade-level passages.

Maintenance tests taken as many as five weeks after instruction had ended showed that the students maintained their use of the strategy and continued to commit fewer oral reading errors than they had before instruction.

Conclusions

After instruction in the Word Identification Strategy, students made substantially fewer decoding errors when reading a passage written at their ability and grade levels than they did before instruction. On average, their comprehension scores increased. However, some students did not realize substantial comprehension score increases.

Reference

Lenz, B.K. and Hughes, C.A. (1990). A Word Identification Strategy for learning disabled adolescents. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 23(3), 149-158, 163.

Study 2

Overview

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of instruction in the Word Identification Strategy on a diverse group of adolescents, some of whom were eligible for special education services. Two matched groups of 62 ninth graders who attended two matched high schools and who had earned decoding scores of two or more grades below their grade level on a standardized decoding test, were involved. Included in the experimental group were 11 students with LD. Many of the students were living in poverty. Both groups included African Americans and Hispanics, as well as Caucasians. The experimental group received instruction in the Word Identification Strategy for 4 to 8 weeks, depending on how much time was required for each student to reach mastery. Students were pulled out of their language arts classes in small groups of 4 to 6 students for the instruction for one hour per day until they met mastery. The comparison group received traditional reading instruction during the school year. All students were tested at the beginning and end of the study using the Slossen Diagnostic Battery (Gnagey & Gnagey, 1994) to obtain a decoding score.

Results

The results showed that ninth-grade students in the experimental school were decoding, on average, at the high fourth-grade level when they entered high school. Seven months later, after the experimental students had received instruction in the Word Identification Strategy, the experimental students were decoding, on average, at the high eighth-grade level, a mean grade-level improvement of 3.4 grade levels. Every student made an improvement of at least .8 grade levels. The eleven students with LD made a mean grade-level improvement of 3.9 grade levels in decoding (range = .8 to 6.1 grade levels). The average decoding level at the beginning of the study for the students with LD was at the 4.9 grade level and at the end of the study was at the 8.8 grade level.

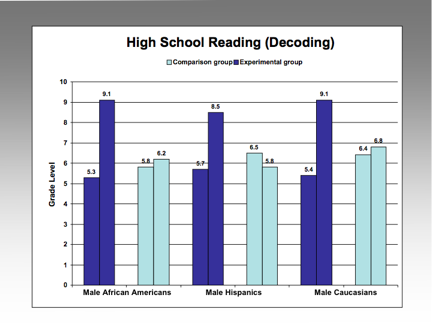

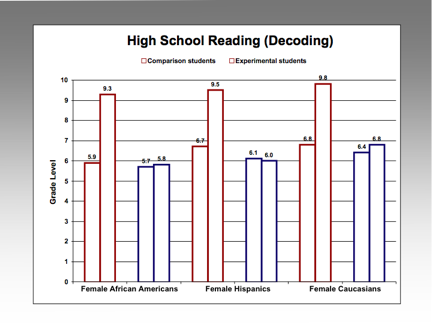

The comparison students made little improvement. At the beginning of the study, they were decoding, on average, at the 6.1 grade level. Seven months later, they were decoding, on average, at the 6.3 grade level, for an average gain of .2 grade levels (range= .1 to 1.7 grade levels). (See Figures 1 and 2, where each pair of bar graphs represents the average pretest and posttest grade level decoding scores. Figure 1 depicts the mean scores for male students; Figure 2 depicts the mean scores for female students.)

Figure 1: Mean grade-level decoding scores for male students

Figure 2: Mean grade-level decoding scores for female students

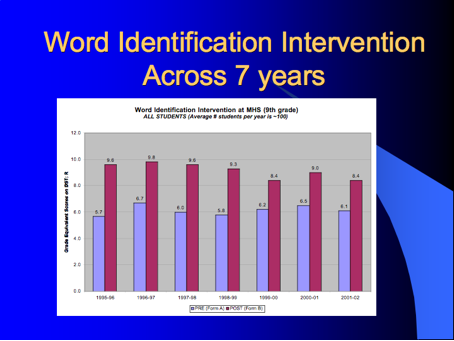

ANCOVA results indicated that there was a significant difference between the posttest raw decoding scores of the experimental and comparison groups [F(1,121) = 31.078, p <.001, η2 = .692] when the pretest scores served as the covariate. (This represents a large effect size). In addition, there was a significant difference between the posttest scores of students with LD in the experimental group and the posttest scores of comparison students who were matched with the students with LD in the experimental group on the basis of their pretest scores [F(1, 19) = 29.673, MSE = 43.93, p < .001, η2 = .610]. (This also represents a large effect size.) However, the most significant finding was that, at the end of the study, the students in the experimental group were decoding, on average, at the ninth-grade level, their actual grade level. The experimental students with LD were decoding at the high eighth-grade level (8.8), very close to their actual grade level. The results for all subgroups of students representing all the minorities, mirrored the results for the whole groups. Furthermore, the authors reported that the same kind of results have been achieved by the school decoding program for eight years running. (See Figure 3 where the blue bars represent pretest scores and the maroon bars represent posttest scores.)

Figure 3: Pretest and posttest grade-level decoding results across school years

Conclusions

Instruction in the Word Identification Strategy, when implemented with small groups of students in an intensive way, can result in “closing the gap” for them with regard to being able to decode multisyllabic words at their grade level. Substantial increases were achieved with all subgroups of students including students with reading disabilities. Comparison students did not make gains in decoding.

Reference

Woodruff, S., Schumaker, J. B., & Deshler, D. D. (2002). The effects of an intensive reading intervention on the decoding skills of high school students with reading deficits. (Research Report No. 15). Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Center for Research on Learning.

Keith Lenz, Ph.D.

Affliations

My Background and Interests

My memories of elementary school are that I did what teachers asked me to do, and that if I did what the teachers asked, school was going as it was intended to go. I didn’t realize that learning was up to me and that I should at some point start assuming some responsibility for my own learning. Around 4th and 5th grade, I started to get into trouble with teachers because I wasn’t doing homework assignments. I really believed that schoolwork was done at school and that homework included all the activities I normally did at home, and they were mostly play activities. I didn’t connect independent effort and responsibility with schoolwork until my 6th grade teacher, Mrs. Mason, began to make the connection very explicit. Needless to say, because my 4th- and 5th-grade learning experiences were very dismal, 6th grade required a lot of hard work to make up for my earlier failures.

In many ways, the feelings of failure that I had in 6th grade have helped me greatly during my career. I know what it feels like to be caught cheating on a math test, face the principal’s grim questions about why none of the first 75 pages of my social studies workbook have been completed, see column after column of D’s and F’s on my report card, and continuously struggle to understand what I was doing wrong in school. Looking back, those early experiences and feelings made me understand what it feels like not to understand how to learn. Not only did I struggle with learning, but I also watched many of my classmates struggle with teachers who taught on the surface without barely a thought or concern about unlocking learning for any of us.

I had to figure out how to learn on my own. I eventually became a teacher myself, teaching at the junior high school, high school, and university levels. As I learned how to teach, those memories of my schooling kept me honest about what I wanted to do in my teaching. Also, when I became a researcher, I realized that I wanted to make learning easy for students. I wanted to develop teaching methods and materials that would help them become good learners.

I will be the first to admit that I have not always been a good learner or a good teacher. However, I have always wanted to be a better learner and a better teacher. Working with my colleagues to develop learning strategy instruction, the Content Enhancement Routines, and other interventions related to strategic instruction has taken me exactly where I know I needed to go in order to help teachers teach better and to help students learn what they need to learn. I know that these are the tools that my teachers needed to use when teaching me years ago.

The Story Behind the Word Identification Strategy

The basic steps of the Word Identification Strategy were originally developed as part of a student project that I completed for a class that I was taking as part of my doctoral studies taught by Dr. Don Deshler. The assignment was to develop a learning strategy that might be taught to students to help them meet a demand that they faced in a secondary school setting. At that time, most of the learning strategies being designed by researchers at the University of Kansas focused on teaching reading comprehension and study strategies. However, my recent experience in the classroom made me wonder what kinds of strategies might be needed to help adolescents who struggled with identifying words in text. The question that nagged me was, “What do you do when you are reading along and you come to a word that you don’t know?”

I began studying the literature that had been written about ways to help students meet this demand, and I began to blend steps and tactics that had been proposed by different educators. After I had finished my project, Don approached me and asked if I would be interested in conducting a study of the effects of instruction in the strategy on students with learning disabilities enrolled in a summer-school program. Over the summer, I worked with Vicky Beals, another doctoral student who was a teacher in the summer school program, to collect data on the strategy with the ongoing support of Jean Schumaker and Don Deshler. Finally, Jean Schumaker took the completed work, developed the DISSECT mnemonic device and drafted the first version of the manual, which was to become one of the first learning strategies manuals to be published as part of the Learning Strategies Curriculum.

My thoughts About Learning Strategies Instruction

I believe that learning strategy instruction is one of the most powerful tools that a teacher can learn about, adopt, and use to improve student learning. Research on strategy instruction continues to demonstrate that significant gains that can be achieved when learning strategies are taught to students. However, since I have also seen learning strategies taught very poorly, I must add that the explicit instruction that is captured by the stages of strategy acquisition and generalization are just as important in defining the effectiveness of these interventions as the steps of each learning strategy. The combination of good learning strategy steps captured in an effective remembering system and then taught explicitly in stages to mastery and for generalization makes these interventions the best tools to improve student learning.

Teacher Feedback on the Word Identification Strategy

Teachers have long reported to me that the Word Identification Strategy is one of their favorite strategies in the Learning Strategies Curriculum. It is often one of the first strategies taught to middle-school students who have developed basic decoding skills but who stall on difficult words as they complete reading assignments. Teachers have reported tremendous growth in reading achievement and in reading confidence as a result of student use of this strategy. In addition, teacher reports continue to support the classroom power and social efficacy of the strategy in the same way that ongoing empirical studies continue to show the benefits of this strategy on student reading scores. Based on the numbers of teachers who have participated in professional development experiences, many thousands of students have benefitted from instruction in this strategy internationally. While a few changes have been made in this strategy and the manual over the years as result of teacher comments and ongoing research, the basic elements associated with the strategy are the same as they were thirty years ago.

My Contact Information

Please contact me at keith.lenz@sri.com

Word Mapping Strategy: Instructor’s Manual

Word Mapping Strategy: Instructor’s Manual