Additional information

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 68 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 1999 |

$15.00

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 68 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 1999 |

Overview

The THINK Strategy is used by cooperative groups to solve problems. The research was conducted in 20 fourth- and fifth-grade general education classes. These intact classes were randomly assigned to the experimental or control conditions. A total of 392 students participated. The 10 teachers of the experimental classes taught their students the SCORE Skills and the THINK Strategy. The 10 control teachers did not teach the SCORE Skills or the THINK Strategy to their students.

Results

Observational data were gathered on the fidelity of the experimental teachers’ implementation of the instruction. They presented a mean of 80% of the information on the SCORE Skills and 95% of the information on the THINK Strategy, according to a checklist based on the two instructor’s manuals.

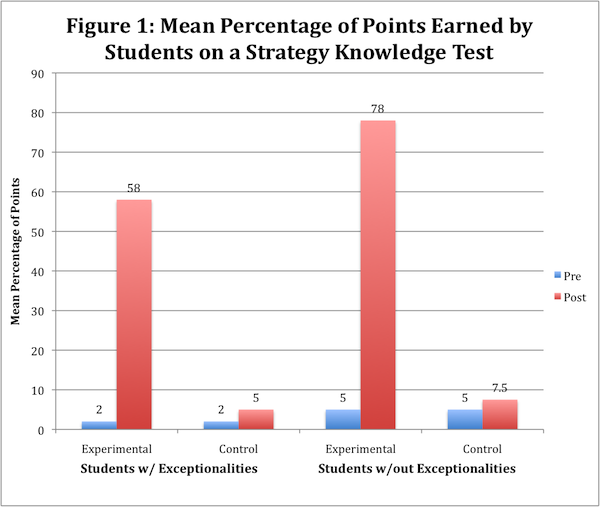

All students in experimental and control classes completed a written test of their knowledge about social skills and problem-solving skills at pretest and posttest. The ANCOVAs revealed significant differences between the posttest scores of experimental and control students for students with exceptionalities, F (1, 19) = 148.03, p < .001, η2 = .90, and for students without exceptionalities, F (1, 19) = 53.36, p < .001, η2 = .76. (These are very large effect sizes.) For students with and without exceptionalities, the adjusted mean for the experimental group was significantly larger than the adjusted mean for the control group. (See Figure 1 for the mean scores.)

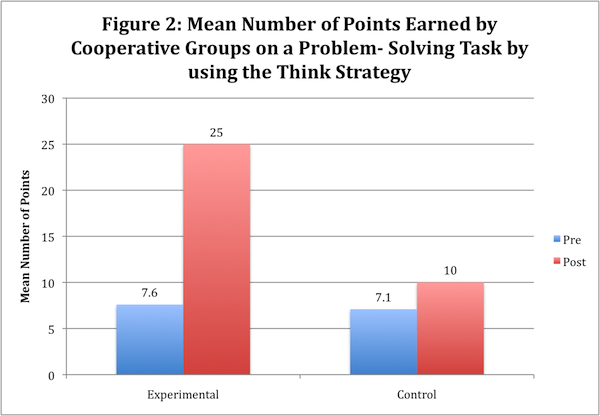

Data were also gathered on the students’ performance as they solved problems together in small groups during the pretest and posttest. Since students with and without exceptionalities worked together in these groups, the analysis was conducted on the combined group means. Observers determined the percentage of strategy steps the students used. The ANCOVA revealed a significant difference between the experimental and control group posttest scores, F (1, 19) = 92.03, p < .001, η2 = .84, a very large effect size. The adjusted posttest mean for the experimental group was significantly larger than the adjusted posttest mean for the control group. (See Figure 2 for the mean scores.)

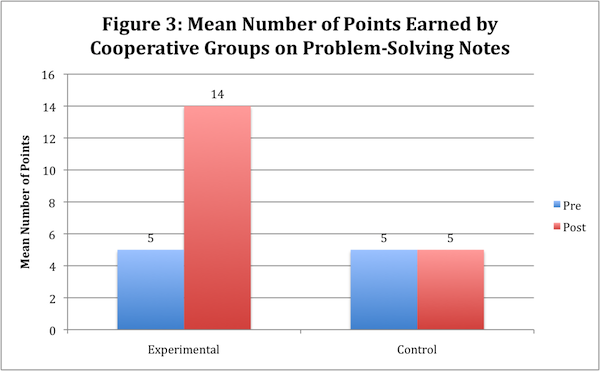

As the students solved problems in their groups, they were to write, on a blank sheet of paper, what was discussed. They earned points according to what they wrote. For example, they earned points for designating a name for the problem, listing background information for the problem, and identifying potential solutions. Again, the ANCOVA was conducted on the combined group means. The ANCOVA revealed a significant difference between the experimental and control group posttest scores, F (1, 18) = 68.25, p < .001, η2 = .81, a very large effect size. The adjusted posttest mean for the experimental group was significantly larger than the adjusted posttest mean for the control group. (See Figure 3.)

Experimental teachers and students used a 7-point Likert-type scale to rate items regarding their satisfaction with the program (“7” indicating extremely satisfied; “1” indicating extremely dissatisfied) at the end of the year. Teachers endorsed the program, and their ratings indicated satisfaction with each aspect of the program. Students also indicated that they were satisfied with the program, with mean scores on items ranging from 5.4 to 5.6. Eighty-six percent of the students recommended that all fourth- and fifth-grade students receive this instruction.

Conclusions

The THINK Strategy instructional program can be successfully used to increase student knowledge about social skills and solving problems with others and to teach students how to solve problems in small cooperative groups. This is an important skill for students who will be faced with solving problems on committees and in meetings and work groups the rest of their lives. Both teachers and students were satisfied with various aspects of the program.

Reference

Vernon, D. S. (1998). Effects of instruction in The THINK Strategy: Progress report. Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Mental Health, SBIR Phase II #R44 MH47211.

D. Sue Vernon, Ph.D.

Affliations

My Background and Interests

By wearing my different hats (a university instructor, a certified teaching-parent, a trainer and evaluator of child-care workers, a SIM professional development specialist, a parent of three children (one with exceptionalities), and a researcher), I have gained knowledge and experience from a number of perspectives. I have a history of working with at-risk youth with and without exceptionalities (e.g., students with learning disabilities, emotional disturbance, behavioral disorders) in community-based residential group-home treatment programs and in schools. I also have extensive experience with training, evaluating, and monitoring staff who work with these populations, and I have conducted research with and adapted curricula for high-poverty populations. In addition to the THINK Strategy program and other Cooperative Thinking Strategies programs, I’ve developed and field-tested interactive multimedia social skills curricula, community-building curricula, communication skills instruction, and professional development programs. I have also developed and validated social skills measurement instruments. As a lecturer of graduate-level university courses in the Department of Special Education at the University of Kansas, I have taught courses designed to enable teachers to access and become proficient in validated research-based practices.

The Story Behind the THINK Strategy

My focus for the last 30 years has been on helping youths learn, and especially on helping them learn how to use social skills. My interest in social skills instruction began when I was a teaching-parent in a group home for adolescents who had a history of social problems. Clearly, those youths had not learned the social skills they needed to be successful in today’s world. Nevertheless, experience showed they could learn to use social skills well, given the right type of instruction. Later, I was the co-founder and Director of Training and Evaluation of the Teaching-Family Homes of Upper Michigan, originally developed through funding from the Michigan State Department of Mental Health and Father Flanagan’s Boys Home. This new agency eventually provided services to over 1,000 youths per day in schools, residential group homes, regional treatment centers, treatment foster homes, schools, and in counseling centers. My primary responsibility in this position was teaching adults (e.g., parents, teachers, foster parents, counselors) to teach social skills to children, and everyday I witnessed these adults successfully teaching the various skills to the youths in their care. Unfortunately, the population receiving instruction was often children who were already involved in the juvenile justice “system.” They were in trouble and had been removed from their homes. As I watched their growing success, I wanted to find a way to introduce social skills instruction as a way to prevent social problems – I wanted to teach children alternative ways of behaving that would help them not only to stay out of trouble but also to create and maintain relationships. I thought the perfect place to prevent problems would be in the general education classroom beginning in elementary school.

As a result, a whole line of research on social skills instruction was born. During early research efforts, I began observing and recording social interactions as students worked in cooperative groups on different types of tasks (and I was appalled at how the students treated one another – especially how other students treated students with exceptionalities). I surveyed teachers and found that they actively supported social skills instruction and were looking for ways to enhance productivity in cooperative groups. They had specific types of tasks in mind that they wanted their students to complete. For example, they wanted their students to successfully solve a complex problem with a team of peers. Thus, my colleagues and I developed and tested the THINK Strategy program in general education classes. Our goal for the Cooperative Thinking Strategy Series was to develop programs that could be used in general education classes and that would benefit students with and without exceptionalities. We wanted students to learn ways to cooperate with each other that they could use in their future lives, such as in post-secondary schools, work, and community situations.

My Thoughts about THINK Strategy Instruction

I have observed the THINK Strategy program being successfully used in schools and in group-home settings with elementary and middle-school students and believe the program can be easily adapted for use in other settings with high school and college students and even adults in business settings. In fact, a professional development specialist mentioned to me that she had structured a meeting with administrators using the steps of the THINK Strategy to solve a couple of problems facing the school district. The administrators discussed the problems in small groups and, after lively and productive conversations about the problems, she then explained more about the structure she had asked them to use. The end result was that district problems were solved and the entire room of administrators wanted the teachers in their schools to learn about and teach the THINK Strategy to students.

After I’ve introduced and taught students in my university classes how to teach the SCORE Skills and THINK Strategy to their students, I ask four-person teams to use the skills and strategy to solve a problem that I assign. I collect “problems” that are featured during that period of time in the local newspaper (e.g., How can schools eliminate hazing?). Creative solutions are found, students enjoy the group activities, and they often mention that they wished the same expectations and structures were in place in their other college courses when cooperative tasks are assigned—especially those tasks involving problem solving.

Teacher and Student Feedback about the THINK Strategy

The State of Kansas accreditation process for all schools mandates that schools develop School Improvement Goals that target at least two major areas each year. One of the two major target areas designated for the state assessment during the time the THINK Strategy field test was conducted was “problem-solving, reasoning, and communication.” Thus, teachers in comparison classes developed their own methods for teaching problem-solving, while teachers in the experimental classes used the THINK Strategy program to teach the skills. While students in all groups increased behaviors related to solving problems, students within the experimental classes made more substantial and significant gains in systematically and methodically generating and evaluating constructive solutions, determining the best solution, and developing an implementation plan. Experimental students almost tripled their problem-solving scores while comparison students increased their scores by less than one point. This increase for experimental students was good news!

Teachers (and students) rated the program highly. Teachers commented, “The THINK Strategy fit right into our class curriculum and style!”, “I feel that it [the Strategy] gave students a ‘formula’ that was easy to remember and follow,” “The THINK Strategy was a breeze and provided some in-depth discussion for my students. I really enjoyed it!!” “I believe each lesson was well worth the time!” When asked what they liked most about the program, the teachers wrote, “It is very organized and easy to teach–all materials are ready. It is well-liked by students,” “I really enjoyed having my students work in teams and evaluate decisions. Some of my students did an incredible job. I was amazed with some of the solutions they brainstormed. I loved how enthusiastic some of my students became,” “I like the way it makes kids think and come up with possible solutions and then rate them.”

When the students were asked what they liked about the THINK Strategy, they wrote, “It helped me to be more social,” “It made it so when I said something they (group members) wouldn’t yell at me,” “I think it is fun and it helps you solve problems better,” “I like the fact that you could use charts or break apart the problem and easily solve it,” “It helps you solve big problems and teaches how to be a better kid,” and “I like it because it’s going to help me solve problems in the future.” Other students indicated that the strategy helps me “… understand the problem,” “…solve more problems faster,” and “…solve other problems, besides the ones my class worked on.” When asked whether they would recommend the program to other fourth and fifth-grade students, 86% of the students said “Yes.” Included in the comments students wrote regarding why others should participate in the program were statements such as, “If they learned how to solve problems (with THINK) they could learn about anything,” “THINK is helpful, easy, and can give a right answer quickly,” “It helps you solve all your problems,” “You learn how fun it is to solve the problem (with THINK),” and “It helps you work with other people.”

My Contact Information

Please contact me at svernon2@windstream.net

Unit Organizer Routine: Instructor’s Manual

Unit Organizer Routine: Instructor’s Manual