Additional information

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 60 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 2000 |

$15.00

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 60 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 2000 |

Overview

The Talking Together Program is used to teach students how to participate in class discussions. The research was conducted in 20 third- and fourth-grade general education classes. These intact classes were randomly assigned to the experimental or comparison condition. A total of 377 students participated. The 10 teachers of the experimental classes taught their students using the Talking Together Program. The 10 comparison teachers did not use this program.

Results

Observational data were gathered on the fidelity of the experimental teachers’ implementation of the instruction. They presented a mean of 91% of the information in the Talking Together instructor’s manual.

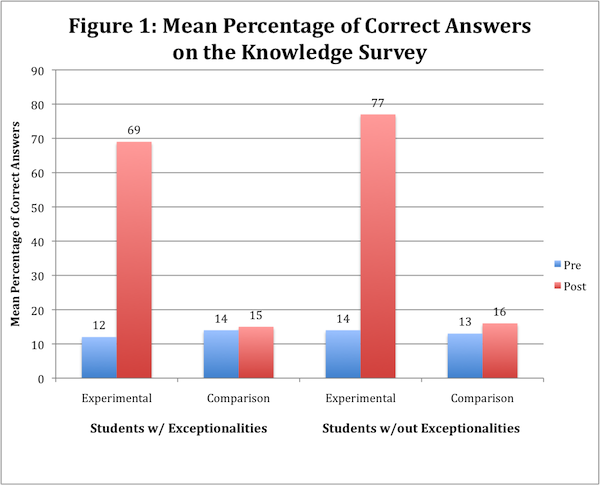

All students in experimental and comparison classes completed a written test of their knowledge about participating in discussions and community building skills at pretest and posttest. An ANCOVA revealed a significant difference between the posttest scores of experimental and comparison students, F (1, 17) = 112.04, p < .001, η2 = .87, representing a very large effect size. (See Figure 1 for the mean scores.)

Data were also gathered on the students’ and teachers’ performances as they participated in class discussions. The ANCOVA for “yell outs” indicated a significant difference between the number of times students yelled out comments or answers between the two groups at the end of the study, F (1,17) = 53.381, p < .001, η2 = .76. The ANCOVA for “group responding” also showed a significant difference between the experimental and comparison groups, F (1, 17) = 9.386, p = .007, η2 = .356, indicating the number of times experimental students participated as a group during the discussion was significantly higher than in comparison classes. The ANCOVA for “partner responding” also showed a significant difference between groups, F (1, 17) = 7.282, p = .015, η2 = .300), indicating the number of times experimental and comparison students discussed answers with partners during the discussion was significantly different during the posttest. The ANCOVA for “negative comments” made by students also indicated a significant difference between the groups, F (1, 17) = 5.005, p = .039, η2 =. 227. Finally, related to teacher behavior, an ANCOVA showed a significant difference between the groups of experimental and comparison teachers for positive comments made by teachers during the posttest discussion, F (1, 17) = 4.864, p = .041, η2 = .222.

Data were also gathered on nine targeted students within each class with regard to such behaviors as raising their hands, waiting quietly to be called upon, and participating. The percentage of times that experimental target students raised their hands and either answered the question or lowered their hands when someone else answered increased from a mean of 14% before intervention to 72% while the mean remained about the same in comparison classes (15% at pretest and 14% at posttest). An ANCOVA indicated the difference between experimental and comparison groups during the posttest discussions was significant, F (1, 17) = 39.74, p < .001, η2 = .70. In addition, ANCOVAs indicated significant differences between experimental and comparison groups during the posttest observation for “yell outs” made by targeted students, F (1, 17) = 10.2, p = .005, η2 = .38, and for the number of participations in the discussion, F (1, 17) = 10.18, p = .005, η2 = .38. All of these differences represent large effect sizes in favor of the experimental classes.

Experimental teachers and students used a 7-point Likert-type scale to rate items regarding their satisfaction with the program (“7” indicating extremely satisfied; “1” indicating extremely dissatisfied) at the end of the year. Teachers endorsed the program, and their ratings indicated satisfaction with each aspect of the program. Their average overall rating of the program was 6.4. Students also indicated that they were satisfied with the program with a mean rating of 5.7.

Reference

Vernon, D.S. (2000). Effects of the Talking Together program: Progress summary. Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, SBIR Phase II #1R44HD34306.

D. Sue Vernon, Ph.D.

Affliations

My Background and Interests

By wearing my different hats (a university instructor, a certified teaching-parent, a trainer and evaluator of child-care workers, a SIM professional development specialist, a parent of three children (one with exceptionalities), and a researcher), I have gained knowledge and experience from a number of perspectives. I have a history of working with at-risk youth with and without exceptionalities (e.g., students with learning disabilities, emotional disturbance, behavioral disorders) in community-based residential group-home treatment programs and in schools. I also have extensive experience with training, evaluating, and monitoring staff who work with these populations, and I have conducted research with and adapted curricula for high-poverty populations. In addition to the Talking Together program and other programs in the Community Building Series, I’ve developed and field-tested the Cooperative Thinking Strategies Series, interactive multimedia social skills curricula, communication skills instruction, and professional development programs. I have also developed and validated social skills measurement instruments. As a lecturer of graduate-level university courses in the Department of Special Education at the University of Kansas, I have taught courses designed to enable teachers to access and become proficient in validated research-based practices.

The Story Behind the Talking Together Program

My focus for the last 30 years has been on helping at-risk youths, particularly in the area of learning and using social skills. My interest in social skills instruction began when I was a teaching-parent in a group home for adolescents who had a history of social problems. One of our major goals in our group home was to make it a safe, respectful place where the youths would feel connected and comfortable while they were learning skills to help them succeed socially and academically. As I watched their growing success, I wanted to find a way to introduce social skills instruction to more children as a way to prevent social problems. I thought the perfect place for this instruction would be in the general education classroom.

Later, as reported school-related tragedies seemed to increase in frequency and become more deadly, I became especially interested in developing ways to prevent bullying and also in ways to create a kinder, more positive classroom environment than was commonly found in public education. A common thread in many interviews with the perpetrators of school violence was not only that they suffered from being bullied most of their lives, but they also felt no connection to their school and the people (e.g., administrators, teachers, or other students) in it.

As a result, two lines of research were born. My first series of research studies focused on social interactions in cooperative groups and resulted in the Cooperative Thinking Strategies Series. The importance of creating a positive, productive learning community in the classroom was part of each program in this series, but teachers indicated that they would like more information about creating learning communities. They wanted their students to be tolerant and supportive, and they wanted a way to systematically teach those concepts and skills to the whole class. As educators, my colleagues and I wanted to help teachers build learning communities where all student learning is supported, especially the learning of students who struggle in school. Thus, we began work on a series of instructional programs focused on the classroom community. Those programs now comprise the Community-Building Series.

We developed and tested the first instructional program, Talking Together, in third-, fourth- and fifth-grade inclusive general education classrooms. We tested the program in those grades to ensure that young students could benefit from the instruction; however, the program has since been used successfully in secondary classrooms as well. Our goal was to develop a program that benefited students both with and without exceptionalities by helping them become engaged and connected learners within a positive, supportive environment. During Talking Together instruction, students learn how to participate in class discussions respectfully and how to support one another. They learn concepts and skills related to controlling their own behavior and expressing respect and kindness towards others. The Talking Together program is the first in the series and is a prerequisite to the other Community-building Series programs. The skills and concepts taught in these programs are foundational to communication within communities, in general, and can be used by students throughout their lives.

My Thoughts About Community-Building Instruction

I have observed the Talking Together program being used successfully with different populations in elementary and middle schools and in group-home settings. I’m always thrilled to see how quickly students can learn to participate together in discussions and treat each other in civil and kinds ways after just a few lessons. I believe the program can be adapted to a variety of settings. For example, when teaching my university classes, we discuss the community that we will create in class, and we specify characteristics that should “always” and “never” be present (that list typically includes some mention of cell phones!). While the community expectations for my college classes are framed differently than the examples in Talking Together, the principles and concepts are nonetheless as important at the university level as they are on the elementary level.

Teacher and Student Feedback about the Talking Together Program

Talking Together is one of our most popular programs. During the summer, I encountered one of my fifth-year general-education teachers in-training from the previous semester who had studied the Talking Together program for a class assignment. She reported that her knowledge of the Talking Together program and my emphasis on learning communities was the key to a local school district’s decision to hire her. Apparently, a major part of the interview involved how she would set up a learning community in her class if hired! Another exciting comment was from a researcher a couple of years ago. He mentioned that as part of a research project in which he was involved, the staff at a middle school implemented the Talking Together program school-wide. The data he collected reflected a dramatic decrease in student disciplinary referrals when the prior year was compared to the years following Talking Together instruction. The staff gave considerable credit to the Talking Together program.

Many teachers at different grade levels have reported that they have successfully used the program. Example teacher comments include, “Teaching a theme of respect, tolerance, and support was excellent. We often expect kids to just magically know how to behave in these ways, but many need to be specifically taught and given chances to practice,” “I loved how the students responded to each other. I feel this program helped them realize the strength of their classmates,” “Many students commented that they wished we had done the program earlier in the year because it taught them how to work with a partner,” “These community-building lessons are for LIFE,” and “I think the program ideals are so valuable to today’s students. They no longer come to school with the values of students in the past…The lessons provide students with a background essential for a quality classroom environment.”

Examples of student comments include, “The program helped me understand people better,” “Before participating in Talking Together, I didn’t like participating in class discussion, but now I do,” and “I am so satisfied with how safe I feel in class. The program actually changed my life.”

My Contact Information

Please contact me at svernon2@windstream.net

Test-Taking Strategy

Test-Taking Strategy