Additional information

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 50 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 2002 |

$15.00

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 50 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 2002 |

Overview

The Taking Notes Together Program is used to teach students how to take notes as well as help their partners take notes. The research was conducted in 20 fourth- and fifth-grade general education classes. These intact classes were randomly assigned to the experimental or comparison condition. A total of 379 students participated, with 190 in the experimental classes and 189 in the comparison classes. The 10 teachers of the experimental classes taught their students using the Taking Notes Together Program. The 10 comparison teachers did not use this program; they provided regularly scheduled instruction.

Results

Observational data were gathered on the fidelity of the experimental teachers’ implementation of the instruction. They presented a mean of 88% of the information in the Note Taking Together instructor’s manual.

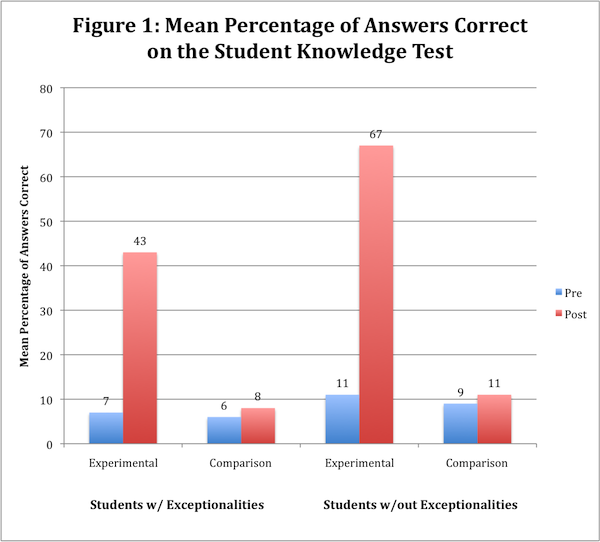

All students in experimental and comparison classes completed a written test of their knowledge about taking notes at pretest and posttest. The ANCOVAs revealed significant differences between the posttest scores of experimental and comparison students with exceptionalities, F (1, 17) = 68.32, p < .001, η2 = .80, and students without exceptionalities, F (1, 17) = 86.91, p < .000, η2 = .84. (These are very large effect sizes.) For students with and without exceptionalities, the mean scores for the experimental group were significantly larger than the mean scores for the comparison group. (See Figure 1 for mean scores.)

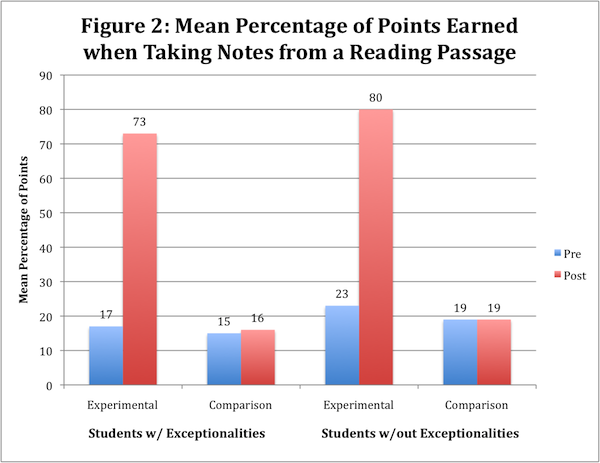

Data were also gathered on the students’ performance as they took notes independently from a reading passage. The ANCOVAs revealed significant differences between the posttest scores of experimental and comparison students with exceptionalities, F (1, 17) = 74.21, p < 0.00, η2 = .81, and students without exceptionalities, F (1, 17) = 109.62, p < .001, η2 = .87. (These are very large effect sizes.) For students with and without exceptionalities, the mean scores for the experimental group were significantly larger than the mean scores for the comparison group. (See Figure 2 for mean scores.)

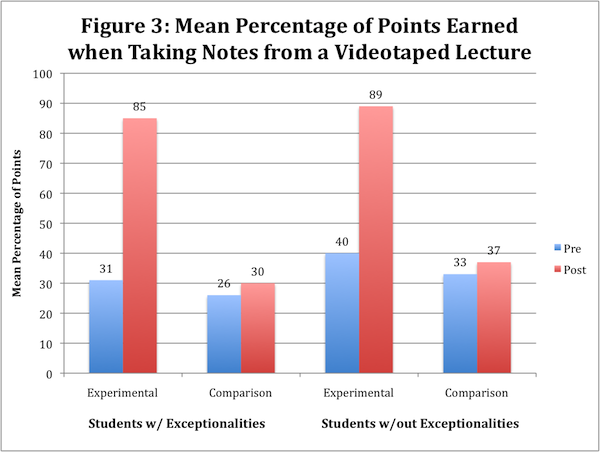

Additionally, data were gathered on the students’ performance as they took notes independently while watching a videotaped lecture. The ANCOVAs revealed significant differences between the posttest scores of experimental and comparison students with exceptionalities, F (1, 17) = 62.04, p < 0.00, η2 = .79, and students without exceptionalities, F (1, 17) = 124.33, p < .001, η2 = .88. (These are very large effect sizes.) For students with and without exceptionalities, the mean scores for the experimental group were significantly larger than the mean scores for the comparison group. (See Figure 3 for mean scores.)

Experimental teachers and students used a 7-point Likert-type scale to rate items regarding their satisfaction with the program (“7” indicating extremely satisfied; “1” indicating extremely dissatisfied) at the end of the year. Teachers endorsed the program, and their ratings indicated satisfaction with each aspect of the program. For example, teachers’ average satisfaction rating for the instructor’s manual was 6.8, for the student materials was 6.9, the ease of use of the program was 6.7, and their overall satisfaction with the program was 6.9. Students also indicated that they were satisfied with the program. Ninety percent of the students recommended that all third-, fourth-, and fifth-grade students receive this instruction.

Reference

Vernon, D.S. (2000). Effects of the Taking Notes Together program: Progress summary. Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, SBIR Phase II #1R44HD34306.

D. Sue Vernon, Ph.D.

Affliations

My Background and Interests

By wearing my different hats (a university instructor, a certified teaching-parent, a trainer and evaluator of child-care workers, a SIM professional development specialist, a parent of three children (one with exceptionalities), and a researcher), I have gained knowledge and experience from a number of perspectives. I have a history of working with at-risk youth with and without exceptionalities (e.g., students with learning disabilities, emotional disturbance, behavioral disorders) in community-based residential group-home treatment programs and in schools. I also have extensive experience with training, evaluating, and monitoring staff who work with these populations, and I have conducted research with and adapted curricula for high-poverty populations. In addition to the Taking Notes Together program and other programs in the Cooperative Thinking Strategy Series, I’ve developed and field-tested the Cooperative Thinking Strategy Series Series, interactive multimedia social skills curricula, communication skills instruction, and professional development programs. I have also developed and validated social skills measurement instruments. As a lecturer of graduate-level university courses in the Department of Special Education at the University of Kansas, I have taught courses designed to enable teachers to access and become proficient in validated research-based practices.

The Story Behind the Taking Notes Together Program

My focus for the last 30 years has been on helping at-risk youths, particularly in the area of learning and using social skills. My interest in social skills instruction began when I was a teaching-parent in a group home for adolescents who had a history of social problems. One of our major goals in our group home was to make it a safe, respectful place where the youths would feel connected and comfortable while they were learning skills to help them succeed socially and academically. As I watched their growing success, I wanted to find a way to introduce social skills instruction to more children as a way to prevent social problems. I thought the perfect place for this instruction would be in the general education classroom.

Later, as reported school-related tragedies seemed to increase in frequency and become more deadly, I became especially interested in developing ways to prevent bullying and also in ways to create a kinder, more positive classroom environment than was commonly found in public education. A common thread in many interviews with the perpetrators of school violence was not only that they suffered from being bullied most of their lives, but they also felt no connection to their school and the people (e.g., administrators, teachers, or other students) in it.

As a result, two lines of research were born. My first series of research studies focused on social interactions in cooperative groups and resulted in the Cooperative Thinking Strategies Series. The importance of creating a positive, productive learning community in the classroom was part of each program in this series, but teachers indicated that they would like more information about creating learning communities. They wanted their students to be tolerant and supportive, and they wanted a way to systematically teach those concepts and skills to the whole class. As educators, my colleagues and I wanted to help teachers build learning communities where all student learning is supported, especially the learning of students who struggle in school. Thus, we began work on a series of instructional programs focused on the classroom community. Those programs now comprise the Community-Building Series. A founding premise associated with all the programs is that students are taught to work together and help each other.

We developed and tested the Taking Notes Together program in third-, fourth- and fifth-grade inclusive general education classrooms to ensure that young students could benefit from the instruction; however, the program has since been used successfully in secondary classrooms as well. Our goal was to develop a program that benefited students both with and without exceptionalities by helping them become engaged and connected learners within a positive, supportive learning environment. In the first lesson of the Taking Notes Together instruction, students review what they have learned in the Talking Together program (the first program in the Community-Building Series) including the prerequisite concepts of participating, working with partners, respect, tolerance and creating a learning community. They review concepts and skills related to controlling their own behavior and expressing respect and kindness towards others. The next three lessons relate to teaching students how to record information quickly and succinctly during lectures, when reading, and when watching videotapes while helping each other. Throughout the program and afterwards, teachers use a framework to deliver information when they want students to take notes.

My Thoughts About Community-Building Instruction

After observing many students not taking notes even when cued by the teacher that the information she was about to say was important for them to know and they should write it down, I realized that many of those students had not developed strategies for listening, organizing, and recording critical information. Students complained that sometimes they did not hear or recognize cues that teachers gave and that sometimes the instructions came AFTER they watched a movie, for example. They reported that they did not know what to look for in the videotape and that they could not remember many details in a discussion after it ended.

These observations and comments prompted us to emphasize the role of both the student and teacher in the note-taking process in the Taking Notes Together program. While students learn a strategy for notetaking and some ways to recognize clues and cues about important information, teachers also prepare lectures around the main ideas and details they want student to identify and understand. Similarly, since most textbooks contain more information than students need to know, teachers provide specific guidelines about the structure of students’ notes (e.g., what topics are most important, how many details should be recorded). Teachers also give students a brief overview of the categories and details that are important for students to note in a videotape or movie before the movie begins.

Teacher and Student Feedback on the Taking Notes Together Program

Teachers and students have been extremely enthusiastic about this program. Example teacher comments include, “The format was very user friendly, great skills for students when reading information text,” “I saw a huge improvement in their note taking skills,” “I enjoyed the program. It also helped with the classroom instruction in other subject areas,” “Love it! Love it! Love it!,” “The skills are logical, educationally sound and age appropriate,” and “I can’t believe how easy you made it for 4th graders to pick up this technique in learning. Not only did they learn a valuable strategy, but also they are so comfortable in helping their classmates.”

Teachers and students have been extremely enthusiastic about this program. Example teacher comments include, “The format was very user friendly, great skills for students when reading information text,” “I saw a huge improvement in their note taking skills,” “I enjoyed the program. It also helped with the classroom instruction in other subject areas,” “Love it! Love it! Love it!,” “The skills are logical, educationally sound and age appropriate,” and “I can’t believe how easy you made it for 4th graders to pick up this technique in learning. Not only did they learn a valuable strategy, but also they are so comfortable in helping their classmates.”

My Contact Information

Please contact me at svernon2@windstream.net

Talking Together: Instructor’s Manual

Talking Together: Instructor’s Manual