Additional information

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 91 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 1999 |

$15.00

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 91 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 1999 |

Overview

The LEARN Strategy is used by cooperative groups to study and learn subject-area information. The research was conducted in 25 fourth- and fifth-grade general education classes. These intact classes were randomly assigned to the experimental or control condition. A total of 519 students participated. The 13 teachers of the experimental classes taught their students the SCORE Skills and the LEARN Strategy. The twelve control teachers did not teach the SCORE Skills or the LEARN Strategy to their students.

Results

Observational data were gathered on the fidelity of the experimental teachers’ implementation of the instruction. They presented a mean of 82% of the information on the SCORE Skills and a mean of 84% of the information on the LEARN Strategy, according to a checklist based on the two instructor’s manuals.

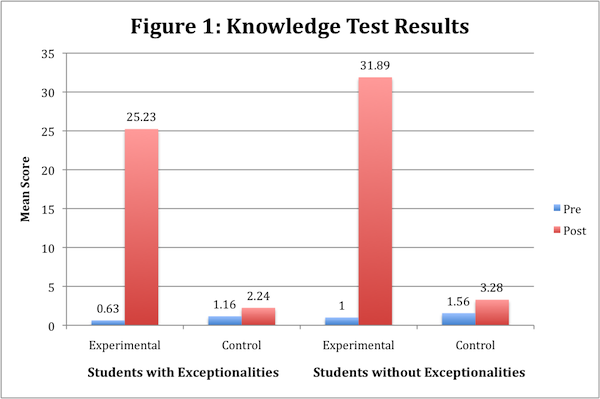

All students in experimental and control classes completed a written test of their knowledge about social skills and how to study for tests before and after the instruction. The ANCOVAs revealed significant differences between the posttest scores of experimental and control students for students with exceptionalities, F (1, 22) = 73.10, p < .001, η2 = .77, and for students without exceptionalities, F (1, 22) = 400.29, p < .001, η2 = .95. (These are very large effect sizes.) For students with and without exceptionalities, the adjusted mean for the experimental group was significantly larger than the adjusted mean for the control group. (See Figure 1 for mean scores.)

Data were also gathered on the students’ performance as they studied information together in small groups during the pretest and posttest. Since students with and without exceptionalities worked together in these groups, analyses were conducted on the combined group means. Observers determined the percentage of strategy steps the students used. The ANCOVA revealed a significant difference between the experimental and control group posttest scores, F (1, 22) = 21.23, p < .001, η2 = .49, a very large effect size. The adjusted posttest mean for the experimental group was significantly larger than the adjusted posttest mean for the control group. For the experimental group, t-test results indicate that students’ performance increased significantly, t (13) = 8.67, p <.001, from a pretest mean of 6.17 to a posttest mean of 21.63. No significant differences were found for comparison students.

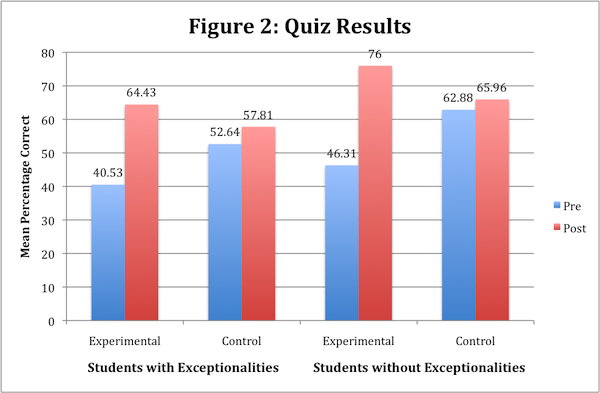

After the students had studied together in their small groups, they took a written quiz independently over the information that they had studied. The ANCOVAs revealed a significant difference between the experimental and control group posttest quiz scores for students with exceptionalities, F (1, 22) = 18.59, p < .001, η2 = .45 (a very large effect size) and for students without exceptionalities, F (1, 22) = 6.22, p = .022, η2 = .22 (a very large effect size). Again, the adjusted posttest mean for the experimental group was significantly larger than the adjusted posttest mean for the control group. (See Figure 2.)

Experimental teachers and students used a 7-point Likert-type scale to rate items regarding their satisfaction with the program (“7” indicating extremely satisfied; “1” indicating extremely dissatisfied) at the end of the year. Teachers endorsed the program, and their ratings indicated satisfaction with each aspect of the program. For example, teachers rated the relevance and benefits of the program in the “very satisfies” range (Mean rating = 6.3). Students also indicated that they were satisfied with the program, with mean scores in the satisfied range.

Conclusions

The LEARN Strategy instructional program can be successfully used to increase student knowledge about social skills and studying with others and to teach students how to study information in small cooperative groups. This is an important skill for students who need the benefits of studying with others. Both teachers and students were satisfied with various aspects of the program.

Reference

Vernon, D. S. (1998). Effects of instruction in The LEARN Strategy: Progress report. Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Mental Health, SBIR Phase II #R44 MH47211.

D. Sue Vernon, Ph.D.

Affliations

My Background and Interests

By wearing my different hats (a university instructor, a certified teaching-parent, a trainer and evaluator of child-care workers, a SIM professional development specialist, a parent of three children (one with exceptionalities), and a researcher), I have gained knowledge and experience from a number of perspectives. I have a history of working with at-risk youth with and without exceptionalities (e.g., students with learning disabilities, emotional disturbance, behavioral disorders) in community-based residential group-home treatment programs and in schools. I also have extensive experience with training, evaluating, and monitoring staff who work with these populations, and I have conducted research with and adapted curricula for high-poverty populations. In addition to the LEARN Strategy program and other Cooperative Thinking Strategies programs, I’ve developed and field-tested interactive multimedia social skills curricula, community-building curricula, communication skills instruction, and professional development programs. I have also developed and validated social skills measurement instruments. As a lecturer of graduate-level university courses in the Department of Special Education at the University of Kansas, I have taught courses designed to enable teachers to access and become proficient in validated research-based practices.

The Story Behind the LEARN Strategy

My focus for the last 30 years has been on helping youths learn, and especially on helping them learn how to use social skills. My interest in social skills instruction began when I was a teaching-parent in a group home for adolescents who had a history of social problems. Clearly, those youths had not learned the social skills they needed to be successful in today’s world. Nevertheless, experience showed they could learn to use social skills well, given the right type of instruction. Later, I was the co-founder and Director of Training and Evaluation of the Teaching-Family Homes of Upper Michigan, originally developed through funding from the Michigan State Department of Mental Health and Father Flanagan’s Boys Home. This new agency eventually provided services to over 1,000 youths per day in schools, residential group homes, regional treatment centers, treatment foster homes, schools, and in counseling centers. My primary responsibility in this position was teaching adults (e.g., parents, teachers, foster parents, counselors) to teach social skills to children, and everyday I witnessed these adults successfully teaching the various skills to the youths in their care. Unfortunately, the population receiving instruction was often children who were already involved in the juvenile justice “system.” They were in trouble and had been removed from their homes. As I watched their growing success, I wanted to find a way to introduce social skills instruction as a way to preventsocial problems – I wanted to teach children alternative ways of behaving that would help them not only to stay out of trouble but also to create and maintain relationships. I thought the perfect place to prevent problems would be in the general education classroom beginning in elementary school.

As a result, a whole line of research on social skills instruction was born. During early research efforts, I began observing and recording social interactions as students worked in cooperative groups on different types of tasks (and I was appalled at how the students treated one another – especially how other students treated students with exceptionalities). I surveyed teachers and found that they actively supported social skills instruction and were looking for ways to enhance productivity in cooperative groups. They had specific types of tasks in mind that they wanted their students to accomplish. For example, in addition to basic interaction skills, they wanted their students to learn how to study together and tutor one another. Thus, my colleagues and I developed and tested the LEARN Strategy program in general education elementary classrooms. Our goal for the Cooperative Thinking Strategy Series was to develop programs that could be used in general education classes and that would benefit students with and without exceptionalities. We wanted students to learn ways to cooperate with each other that they could use in their future lives, such as in post-secondary schools, work, and community situations.

My Thoughts about LEARN Strategy Instruction

I have observed the LEARN Strategy program being successfully used in schools and in group-home settings with elementary and middle-school students and believe the program can be easily adapted for use in other settings especially with high school and college students where students are required to memorize large amounts of information. This was an especially fun strategy to observe students using because the student teams developed such creative memory devices. In one class, I observed the students learning what states were in each region in the U.S., the capitals of all 50 states, resources within the states, and so on. In one activity, teams were assigned regions and were asked to use the LEARN Strategyy to create a memory device for remembering the states within their region. Once they became experts on their region, all of the teams split up and took turns teaching their memory device to other teams. The activity was a success. The teacher told me it was the first time in 20 years of teaching that 100% of her students received a perfect 100% score on the test covering the states and regions. She also mentioned that she surveyed her students each year about their experience in fourth grade. On the question asking what was their favorite part of fourth grade, five or six students answered “learning the LEARN Strategy.”

In teaching my university classes after I’ve introduced and taught my students how to teach the SCORE Skills and LEARN Strategy to their students, I give four-person teams a page of information that I have collected from Science and History textbooks related to a variety of topics. I ask them to practice using the LEARN Strategy to organize the information and create memory devices. Through the years, my graduate students have created especially entertaining memory devices! Almost all my university students comment that not only will they teach their students how to use the LEARN Strategy, but they will use it individually and with study partners as they complete their advanced degrees.

Teacher and Student Feedback on the LEARN Strategy

Comments from teachers about what they have liked most about the program include “The LEARN Strategy addresses a very weak area in our curriculum and has great potential for empowering students to learn more successfully”; “I am thrilled that I have another way to help my students succeed”; “It was so useful, the kids really liked using it, and they had fun.” Student comments related to the LEARN Strategy included, “I have a better memory now,” “It gave me a B+ in social studies,” “It helped me do reports and homework better,” “It helps you remember things when you study,” and “It helped me study for tests and understand things easier.”

My Contact Information

Please contact me at svernon2@windstream.net

Learning Express-ways Communication System

Learning Express-ways Communication System