Description

Research on the Inference Strategy Program

Study 1

Overview

The Inference Strategy is used by students to answer inferential questions about a reading passage. It is also used by students to ask and answer their own inferential questions. Two studies have been conducted on this program. In the first study, 8 ninth graders with disabilities (7 with LD, 1 with developmental disabilities) participated in a multiple-baseline across-students design. Six of the students qualified for free or reduced-price lunches. All eight students received small-group instruction in the strategy in a resource room.

Results

Several measures were gathered in this study. Students took a series of tests. The strategy-use test required them to analyze and categorize literal and inferential questions related to a passage and find clues in the passage related to the questions. The criterion-based comprehension test required them to read a passage and answer literal and inferential questions about that passage. The GRADE test was a standardized test of reading comprehension that requires students to answer literal and inferential questions about a passage.

With regard to strategy use, prior to instruction, the students used an average of 0% of the behaviors included in the strategy. During instruction, they used an average of 66% of the behaviors. After instruction, they used an average of 82% of the strategy behaviors. A Friedman Test and follow-up comparisons indicated that there was a significant difference between the students’ baseline and post-instruction strategy-use scores (p = .012).

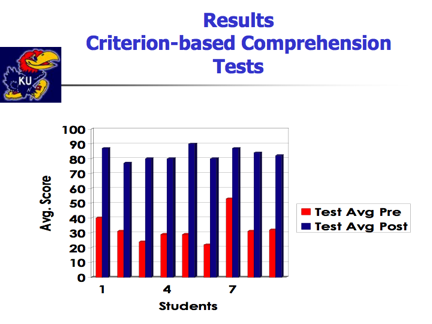

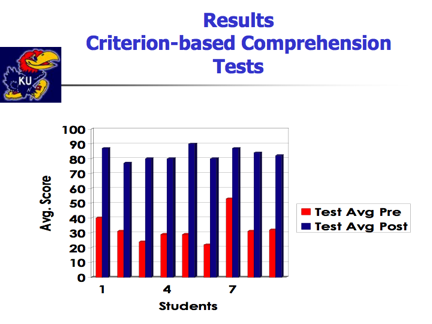

With regard to the criterion-based comprehension test, Figure 1 shows the results. The mean baseline comprehension test score was 32%. During instruction, the students answered a mean of 77% of the questions correctly. The mean post-instruction comprehension score was 82%. The mean test score on the maintenance test administered after students had completed the whole program was 78.67%. Again, statistical tests indicated that the post-instruction scores were significantly different from the baseline scores (p = .012).

Figure 1: Percentage Correct on Criterion-based Comprehension Tests

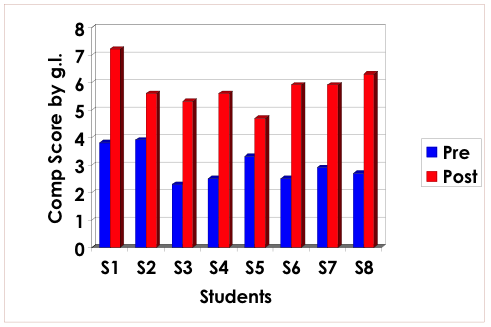

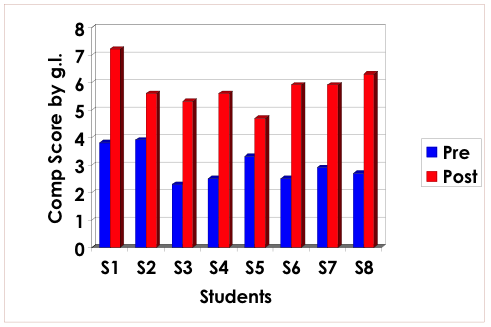

With regard to the GRADE scores, students made an average gain of 2.8 grade levels on this test. (See Figure 2 for individual scores.) Again, a significant difference was found between the pretest and posttest scores (p = .012), and the effect size was large (r = .91).

Figure 2: Grade-Level Scores on the Reading Comprehension Subtest of the GRADE.

Reference

Fritschmann, N. S., Deshler, D. D., & Schumaker, J. B. (2007). The effects of instruction in an inference strategy on the reading comprehension skills of adolescents with disabilities. Learning Disabilities Quarterly, 30(4), 244-264.

Study 2

Overview

Study 1 focused on the instruction of students with disabilities in small groups in a resource room. In contrast, Study 2 focused on the instruction of large groups of students in general education classes by general education teachers. A total of 13 general education teachers were randomly assigned within their teams to teach either the Inference Strategy or the Sentence Writing Strategy to their regularly assigned sixth-grade classes. The teachers who were randomly assigned within their teaching teams to the Inference Strategy condition taught the Inference Strategy to a total of 14 general education classes. A total of 529 students participated in the study, with 316 students receiving Inference Strategy instruction, and 213 students receiving writing strategy instruction. Results were analyzed for two subgroups of students within these larger groups as well as for the larger groups. Within the disabilities subgroup, a total of 28 students with disabilities received the Inference Strategy instruction, and 23 students with disabilities received the writing strategy instruction. These students were included in general education classes for most of the school day. Students with LD, students with speech and language deficits, and students with disabilities in other mild-to moderate categories comprised this group. Within the poor comprehenders group (those who scored below the 40th percentile on the reading comprehension subtest of the GRADE), 84 students were in the experimental group, and 55 students were in the control group.

Results

Among the instruments used were: (a) a test of student knowledge of the Inference Strategy and associated concepts, (b) a test of student use of the Inference Strategy to answer inferential questions (a combined strategy-use/comprehension measure), (c) a test of student use of the Inference Strategy to generate and answer their own inferential questions, and (d) the reading comprehension subtest of the GRADE.

The hierachical linear model approach with SAS PROC MIXED was used to compare the posttest scores of the experimental and control students for the strategy knowledge and strategy use measures. The students were nested within classes within the analyses, and pretest scores were used as the covariate in each analysis. For the whole group of students, for students with disabilities, and for poor comprehenders, a significant difference was found between the posttest scores of the experimental and control students on the strategy knowledge measure [F(1, 24.70) = 469.64, p < .0001; F(1, 9.98) = 48.00, p < .0001; F(1, 23.3) = 199.18, p < .0001, respectively] and the strategy-use measure [F(1, 24.1) = 56.34, p < .0001; F(1, 14.3) = 13.17, p = .0026; F(1, 25.5) = 42.54, p < .0001] in favor of the experimental students. For example, after instruction, both subgroups of the students with disabilities and the poor comprehenders in the experimental classes earned a mean of 20 points while the whole group of students in experimental classes earned a mean of 23 points on the strategy-use test. In contrast, the comparison students with disabilities and poor comprehenders both earned a mean score of 7 points while the whole group of comparison students earned a mean score of 10 points on the strategy-use posttest.

With regard to a test where the students had to create and answer their own inferential questions, again, statistically significant differences were found between the experimental and control students in all three student groups in favor of the experimental group: total sample [F(1, 24.4) = 79.02, p < .0001]; poor comprehenders [F(1, 24.3) = 24.78, p < .0001]; and students with disabilities [F(1, 8.76) = 12.5, p < .0066].

With regard to the GRADE standardized reading comprehension subtest, students in the experimental group as a whole made a significant gain between the pretest and posttest [F(1, 609) = 22.18, p < .0001]. Poor comprehenders also made a significant gain [F(1, 155) = 6.70, p =.0106]. Students with disabilities did not make a significant gain [F(1,37.3) = 1.19, p =.2825].

Conclusions

Thus, Inference Strategy instruction has been successfully provided within both resource rooms and general education classes with different-sized student groupings. In both settings, students benefited from the instruction in that they gained skills which they could apply to reading passages. In the resource room, students with disabilities mastered the strategy such that they could make significant gains on a standardized reading comprehension test. In the general education classroom, students with disabilities did not make significant gains on the same standardized test. Nevertheless, the whole group of students and poor comprehenders did make significant gains on the standardized test of reading comprehension after only six weeks of instruction. Thus, small-group instruction may be required by students with disabilities if they are to master the Inference Strategy and make significant reading gains on standardized tests.

Reference

Fritschmann, N. S., Schumaker, J. B., & Deshler, D. D. (in prep.). Strategic inference instruction in general education settings. Lawrence, KS: Edge Enterprises, Inc.

About the Author

Nanette S. Fritschmann, Ph.D.

Affliations

Assistant Professor

Lehigh University

Certified SIM Professional Development Specialist

University of Kansas Center for Research on Learning

My Background and Interests

First and foremost, like many of my fellow educators, I feel a deep desire to use my gifts and talents to serve those who are in need. I believe this desire grows out of many of my personal life experiences. For example, as a young person, I was drawn to volunteer at a therapeutic equine program that served people of various cognitive and physical disabilities. From a young age, I got a sense of the tremendous determination of people with disabilities, and I learned that, with the right support, all things are possible. I became a teacher of students with disabilities in various settings and realized that although many positive things were happening in our classrooms, there were other things that could be better. My work focused on students with learning disabilities and those who were at risk for academic failure which often included students representing minority populations and/or students who were English language learners. I began to develop a desire to address instructional issues within our secondary schools that were becoming more apparent as our educational environments have continued to shift. After becoming a mother, my desire to impact the academic experience of youths in a positive way has become the focus of my life’s work. I am committed to helping those who need it the most.

The Story Behind the Inference Strategy

As a classroom teacher, I had become increasingly concerned that the many students with mild/moderate learning disabilities whom I had the pleasure of knowing were not learning at the rate and pace that would allow them to feel successful academically. In this role, I began to observe how many teachers often felt that they didn’t have the skills or tools to address the needs of such students. I longed to find better, more effective teaching techniques to allow all students to learn. I began to use the Learning Strategies Curriculum to meet the specific needs of my students. Various students not only began to be successful with academic tests in school (i.e. vocabulary tests, reading quizzes, etc.), but they actually began to generalize complex thinking skills outside of the academic environment. I became inspired to address issues that were becoming increasingly important in our current educational environment. This experience as a teacher started me on the path that would lead me to develop the Inference Strategy.

With the expansion of standards-based reform and assessment-based accountability commonplace in our nation’s schools, I began an attempt to understand what types of skills our students were being asked to demonstrate. Through my research and the work of colleagues, a pattern began to appear. I learned that all students are being held accountable for using specific reading comprehension skills. Two main categories of comprehension processes are required: those at the literal level and those at the inferential level. I also began to observe the various ways that teachers addressed these types of skills in both elementary and secondary classrooms. As expected, elementary teachers addressed many of the requisite skills using a variety of techniques and practices. In contrast, given the focus of presenting content in secondary learning environments, reading instruction was not a focus of instructional time in secondary classes. Based on these understandings, I began to develop a method for teachers to use to provide explicit, systematic instruction in literal and inferential comprehension processing to give all students the skills they need to be successful. My goal was to develop an instructional program that could be used within typical English language arts classes that was aligned with current educational practices and content standards.

My Thoughts about Inference Strategy Instruction

I have been fortunate enough to observe teachers with various levels of experience in different regions of the country teach the Inference Strategy to their students with and without disabilities in both middle- and high-school settings. Each time, I have seen students engaged and interested in applying a strategic method to reading materials that they may have considered unapproachable in the past. I have seen students with disabilities and underperforming students celebrate their improvements in reading and “show off” their improved performance or scores. I believe that today’s educators are facing tough challenges each and every day and that we must find a way to address these challenges in the most efficient manner possible. I believe that the Inference Strategy program is a program that does just that.

Teacher and Student Feedback on the Inference Strategy Instruction

By and large, the feedback from teachers who have implemented instruction in this strategy has been extraordinarily positive! Also, teachers have commented on how this program is really a combination of skills that many other programs address. The difference between this program and others is that this program is a way to address the various levels and combinations of skills that our diverse learners bring to our classrooms. Also, teachers have commented on how the program helps them to structure their discussion around reading materials in order to maximize instructional time. Teachers have reported a deeper understanding of higher level reading comprehension processes, which in turn has helped them teach more effectively. Further, students have made statements like, “Finally, here is something that will help me get through this stuff!”

My Contact Information

Nanette S. Fritschmann, Ph.D.

The College of William and Mary

301 Monticello Ave.

Williamsburg, VA 23187

757 221-6201

nfritschmann@wm.edu