Additional information

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 75 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 1996 |

$15.00

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 75 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 1996 |

Overview

The Teamwork Strategy is used by cooperative groups to complete a group project. The SCORE Skills are basic social skills used during each cooperative-group activity. The research was conducted in a total of six classrooms, two each at the fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-grade levels. Members of these three pairs of intact classes were randomly assigned to the experimental or control condition. A total of 115 students received parental consent to participate, with 57 students enrolled in the experimental classes and 58 students in the control classes. The three teachers of the experimental classes taught their students the SCORE Skills and the Teamwork Strategy. The three control teachers did not teach the SCORE Skills or the THINK Strategy to their students. The performance of two groups of students was monitored: target students and all other students. Target students were students with exceptionalities who were receiving educational services for their disability and/or skill deficits.

Results

Observational data were gathered on the fidelity of the experimental teachers’ implementation of the instruction. They presented a mean of 95% of the information on the SCORE Skills and the Teamwork Strategy, according to a checklist based on the two instructor’s manuals.

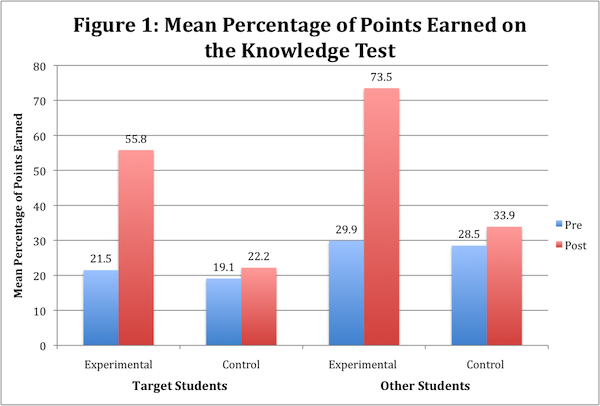

All students in experimental and control classes completed a written test of their knowledge about social skills and teamwork skills at pretest and posttest. The ANCOVAs revealed significant differences between the posttest scores of experimental and control students for students with exceptionalities, F (1, 15) = 13.84, p < .002, η2 = .48, and for students without exceptionalities, F (1, 84) = 129.83, p < .001, η2 = .61. (These are very large effect sizes.) For students with and without exceptionalities, the adjusted mean for the experimental group was significantly larger than the adjusted mean for the control group. (See Figure 1 for mean scores.)

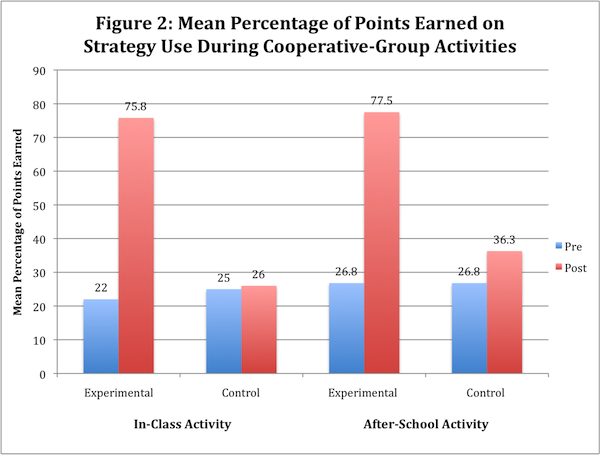

Data were also gathered on the students’ performance as they completed projects together in small groups during the pretest and posttest. Since students with and without exceptionalities worked together in these groups, the analysis was conducted on the combined group means. Observers determined the percentage of social skills and strategy steps the students used. The ANCOVA on the in-class project revealed a significant difference between the experimental and control group posttest scores, F (1, 16) = 53.24, p < .001, η2 = .77, a very large effect size. The ANCOVA on the out-of-class project (a generalization task) also revealed a significant difference between the experimental and control group posttest scores, F (1, 16) = 38.26, p < .001, η2 = .70, also a very large effect size. The adjusted posttest mean for the experimental group was significantly larger than the adjusted posttest mean for the control group in each case. (See Figure 2 for mean scores.)

Experimental teachers and students used a 7-point Likert-type scale to rate items regarding their satisfaction with the program (“7” indicating extremely satisfied; “1” indicating extremely dissatisfied) at the end of the year. Teachers endorsed the program, and their ratings indicated satisfaction with each aspect of the program. For example, teachers’ average satisfaction rating for “relevance of the program to your students” was 6.3, “students benefited from the instruction” was 6.0, “students got along better after the instruction” was 6.3, and “the steps of the Teamwork Strategy were relevant for the students” was 6.0. Students also indicated that they were satisfied with the program, with mean scores on most items ranging from 5.0 to 6.0. One hundred percent of the fourth and fifth graders recommended that all fourth- or fifth-grade students receive this instruction.

Conclusions

The SCORE Skills and Teamwork Strategy instructional programs can be successfully used to increase student knowledge about social skills and completing group tasks and to teach students how to complete group projects successfully in small cooperative groups. This is an important skill for students who will be faced with completing group tasks in work teams the rest of their lives. Both teachers and students were satisfied with various aspects of the program.

Reference

Vernon, D. S. (1998). Effects of instruction in The SCORE Skills and the Teamwork Strategy: Progress report. Washington, D.C.: National Institute of Mental Health, SBIR Phase II #R44 MH47211.

D. Sue Vernon, Ph.D.

Affliations

My Background and Interests

By wearing my different hats (a university instructor, a certified teaching-parent, a trainer and evaluator of child-care workers, a SIM professional development specialist, a parent of three children (one with exceptionalities), and a researcher), I have gained knowledge and experience from a number of perspectives. I have a history of working with at-risk youth with and without exceptionalities (e.g., students with learning disabilities, emotional disturbance, behavioral disorders) in community-based residential group-home treatment programs and in schools. I also have extensive experience with training, evaluating, and monitoring staff who work with these populations, and I have conducted research with and adapted curricula for high-poverty populations. In addition to the SCORE Skills program and other Cooperative Thinking Strategies programs, I’ve developed and field-tested interactive multimedia social skills curricula, community-building curricula, communication skills instruction, and professional development programs. I have also developed and validated social skills measurement instruments. As a lecturer of graduate-level university courses in the Department of Special Education at the University of Kansas, I have taught courses designed to enable teachers to access and become proficient in validated research-based practices.

The Story Behind the SCORE Skills

My focus for the last 30 years has been on helping youths learn, and especially on helping them learn how to use social skills. My interest in social skills instruction began when I was a teaching-parent in a group home for adolescents who had a history of social problems. Clearly, those youths had not learned the social skills they needed to be successful in today’s world. Nevertheless, experience showed they could learn to use social skills well, given the right type of instruction. Later, I was the co-founder and Director of Training and Evaluation of the Teaching-Family Homes of Upper Michigan, originally developed through funding from the Michigan State Department of Mental Health and Father Flanagan’s Boys Home. This new agency eventually provided services to over 1,000 youths per day in schools, residential group homes, regional treatment centers, treatment foster homes, schools, and in counseling centers. My primary responsibility in this position was teaching adults (e.g., parents, teachers, foster parents, counselors) to teach social skills to children, and everyday I witnessed these adults successfully teaching the various skills to the youths in their care. Unfortunately, the population receiving instruction was often children who were already involved in the juvenile justice “system.” They were in trouble and had been removed from their homes. As I watched their growing success, I wanted to find a way to introduce social skills instruction as a way to prevent social problems – I wanted to teach children alternative ways of behaving that would help them not only to stay out of trouble but also to create and maintain relationships. I thought the perfect place to prevent problems would be in the general education classroom beginning in elementary school.

As a result, a whole line of research on social skills instruction in classrooms was born. During my dissertation research, I began observing and recording social interactions as students worked in cooperative groups (and I was appalled at how the students treated one another – especially how other students treated students with exceptionalities). I surveyed teachers and found that they actively supported social skills instruction and had specific types of skills in mind that they wanted their students to learn. For example, they wanted their students to learn some basic interaction skills, so the students could productively complete a cooperative learning activity. They also wanted a way to systematically teach those skills to the whole class. Thus, my colleagues and I developed and tested the SCORE Skills program in general education classrooms. Our goal was to develop a program that benefited students with and without exceptionalities. The SCORE Skills are five basic social skills that can be used anywhere to develop good relationships with others. Additionally, they are especially useful when involved in cooperative activities. Thus, they are the foundation skills for the other Cooperative Thinking Strategies, like the THINK Strategy, the LEARN Strategy, the BUILD Strategy, and the Teamwork Strategy. They should be learned by students before they learn the other Cooperative Thinking Strategies.

My thoughts about SCORE Skills Instruction

I have observed the SCORE Skills program being used with different populations in elementary and middle schools and in group-home settings. I believe the program can be adapted to a variety of settings. Several years ago, a graduate student did research using the SCORE Skills program with adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder. She has been successfully using the program with this population since receiving her Ed.D., her research has been published, and she has presented her experiences and research results at national and international conferences. In teaching my university classes, if I am assigning cooperative tasks, I always spend time outlining my expectations for how the group members should work together. While those expectations are framed differently (e.g., instead of “sharing,” I may talk about “synthesizing”), they are nevertheless a slightly more sophisticated variation of the SCORE Skills. I believe there are many individuals (including adults) who can benefit from social skills instruction.

Teacher and Student Feedback about SCORE Skills Instruction

Students and teachers have told me and other staff members that this is a popular program. When we asked students in two fourth-grade classrooms if they would like to tell us on camera about their experience with the SCORE Skills program that semester, all eight students with exceptionalities volunteered. Their comments have become part of the SCORE Skills Professional Development CD. My favorite comment was from a student who had significant peer relationship problems before participating in the program. He told us that he loved the SCORE Skills, that he was busy teaching them to his family, and that “if everyone used the SCORE Skills, the world would be a better place.”

My Contact Information

Please contact me at svernon2@windstream.net

Self-Questioning Strategy: Instructor’s Manual

Self-Questioning Strategy: Instructor’s Manual