Additional information

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 42 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 1994 |

| Requirements |

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 42 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 1994 |

| Requirements |

Study 1

Overview

The Concept Anchoring Routine is a set of procedures teachers use to plan and deliver information to students about a major concept that is foundational to a unit of study. The key to this routine is relating the new concept to a concept with which students are already familiar. The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of the routine on student learning. A total of 83 students participated. They were enrolled in eight science classes which were randomly assigned to either Condition 1 (n = 39) or Condition 2 (n = 44). The performance of four subgroups of students was monitored: high achievers (HA), normal achievers (NA), low achievers (LA), and students with learning disabilities (LD).

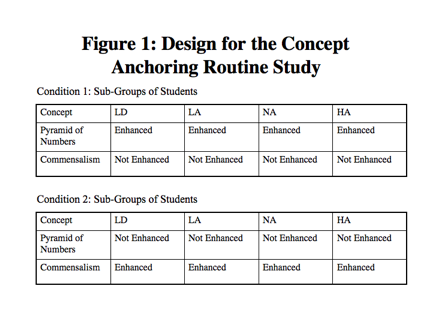

Two concepts were chosen as the targets of the instruction: commensalism and pyramid of numbers. Both concepts were instructed in both conditions; however, in Condition 1, commensalism was taught using the Concept Anchoring Routine, while in Condition 2, pyramid of numbers was taught using the routine. When the routine was used, the concept was called the “enhanced concept.” A counterbalanced design was used with one concept being taught using the routine and one concept being taught with traditional lecture methods in each condition and then flip-flopping the concepts and the type of instruction for the other condition. Figure 1 displays the design. A researcher who was a certified teacher provided the instruction.

A 32-item multiple-choice test served as the outcome measure. Items on the test related to information associated with the two taught concepts: commensalism and pyramid of numbers. A student’s score was the percentage of items answered correctly on the test.

Results

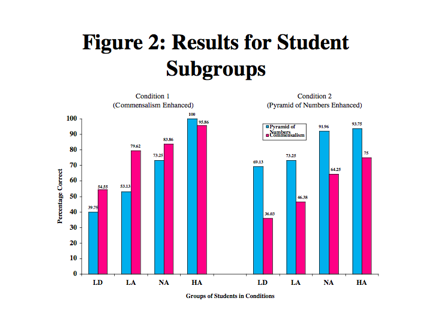

Figure 2 displays the results of the study for the different subgroups of students on a test over the information related to the two concepts. The pink bars show the results for the commensalism concept, and the blue bars show the results for the pyramid of numbers concept. In essence, with one exception (when high achievers were taught about commensalism), all of the subgroups earned higher scores on the test when the routine was paired with the concept than when traditional instruction was paired with the concept. For example, when students with LD participated in the routine, they earned an average test score of 69% on Pyramid of Numbers items and 55% on Commensalism items. When they did not participate in the routine, they earned an average test score of 36% on Pyramid of Numbers items and 40% on Commensalism items.

For the student groups as a whole, students who participated in the routine earned significantly higher scores on the test items than those who did not: Commensalism [F(1, 81) = 20.03, p = .000]; Pyramid of Numbers [F(1,81) = 9.12, p = .001].

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that use of the Concept Anchoring Routine by a researcher providing instruction to students can enhance student performance on researcher-made tests. All subgroups of students benefited from the use of the routine with the exception of the high-achieving students in relation to one of the concepts.

References

Bulgren, J. A., Deshler, D. D., Schumaker, J. B. & Lenz, B.K. (2000). The use and effectiveness of analogical instruction in diverse secondary content classrooms.Journal of

Educational Psychology, 92(3), 426-441.

Deshler, D. D., Schumaker, J. B., Bulgren, J. A., Lenz, B. K., Carnine, D., Grossen, B., Jantzen, J. E. (2002). Teaching students with LD how to master difficult content by anchoring it

to what they know. Teaching Exceptional Children.

Study 2

Overview

The purpose of this investigation was to determine the effects of professional development workshops on teacher use of the Concept Anchoring Routine. Ten general education teachers of subject-area courses participated, and each teacher targeted one class. A total of 193 students participated in the targeted classes. A checklist was used to measure teacher use of the routine during regularly scheduled classes. Items on the checklist corresponded to the behaviors teachers should emit as they implement the routine. The teacher’s score was the percentage of behaviors on the checklist that the observer witnessed and recorded on the checklist. A multiple-baseline across-teachers design was used.

Results

During baseline (before instruction), the teachers performed a mean of 4% of the behaviors on the checklist. After instruction, the teachers performed a mean of 94% of the behaviors as they were using the routine in their classes with the students.

Conclusion

The teachers learned to use the Concept Anchoring Routine in a relatively short amount of time at mastery levels. In fact, all but one teacher exceeded the mastery level the first time that they used the routine in class. Once they attained that level, they maintained it.

References

Bulgren, J. A., Deshler, D. D., Schumaker, J. B. & Lenz, B.K. (2000). The use and effectiveness of analogical instruction in diverse secondary content classrooms.Journal of

Educational Psychology, 92(3), 426-441.

Deshler, D. D., Schumaker, J. B., Bulgren, J. A., Lenz, B. K., Carnine, D., Grossen, B., Jantzen, J. E. (2002). Teaching students with LD how to master difficult content by anchoring it

to what they know. Teaching Exceptional Children.

Study 3

Overview

The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of teacher use of the Concept Anchoring Routine on student learning. One of the ten teachers who participated in Study 2 volunteered for this study. Eighteen of the students in one of her seventh-grade life-science classes volunteered as well. An ABAB reversal design was used. The teacher chose four concepts to be taught. She used the routine to teach the first and third concepts. The second and fourth concepts were taught using a traditional lecture-discussion format. A nine-item test was administered by the teacher the day after each concept was taught. The four tests were designed to have parallel open-ended questions focused on the concept that had just been taught.

Results

After the first concept, epiglottis, was taught using the routine, the students earned a mean score of 83% on the test. After the second concept, pancreas, was taught with traditional methods, the students earned a mean score of 27%. After the third concept, alveoli, was taught through the use of the routine, the students earned a mean score of 70%. After the fourth concept, esophagus, was taught through traditional methods, the students earned a mean score of 42%. A significant difference was found between the test scores associated with the routine and the test scores associated with traditional methods in favor of the scores earned after the routine had been used [t(34) = 9.11, p < .000].

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that teacher use of the routine in an actual life-science class was associated with enhanced learning by students. Students earned higher scores on specially designed concept tests after they had participated in the routine versus traditional instruction.

References

Bulgren, J. A., Deshler, D. D., Schumaker, J. B. & Lenz, B.K. (2000). The use and effectiveness of analogical instruction in diverse secondary content classrooms.Journal of

Educational Psychology, 92(3), 426-441.

Deshler, D. D., Schumaker, J. B., Bulgren, J. A., Lenz, B. K., Carnine, D., Grossen, B., Jantzen, J. E. (2002). Teaching students with LD how to master difficult content by anchoring it

to what they know. Teaching Exceptional Children.

Janis Bulgren, Ph.D.

Affliations

My Background and Interests

The focus of my research has been developing ways to help adolescents, including those with disabilities, succeed in inclusive general education classes. Having two degrees in English and teaching at the high school level for several years made me very aware of the needs of both teachers and students in diverse subject-area classes. This led to me to pursue a degree in special education from the University of Kansas. My combined background of general education and special education has allowed me to pursue my interests and insights about how teachers teach and how students learn. As a result, I have been privileged to work with teachers in a variety of subject areas and to do research on instructional techniques that support all students, including those who are low achieving, average achieving, and high achieving, as well as students with disabilities.

My focus has been on a programmatic line of research that builds upon a foundation of knowledge of factual information to create an understanding of critical concepts, to enable manipulation of information including making comparisons, analyzing causes and effects, weighing options to make decisions, and using reasoning to analyze claims and arguments. The goal of the instructional practices that my colleagues and I have designed is to guide students as they engage in deep learning and comprehension across subject-area domains and ultimately in the generalization of thinking to subject-area and real-world issues.

The Story Behind the Concept Anchoring Routine

The development of the Concept Anchoring Routine followed shortly after the development of the Concept Mastery Routine, and it is a logical extension of understandings about how students learn. Although the exploration of characteristics and examples related to a major concept was a common and well-researched approach to helping students acquire an understanding about that critical concept, there appeared to be other paths for achieving this. One of these was teaching by analogy. In fact, the original working name for the Concept Anchoring Routine was the “Analogical Anchoring Routine.” Therefore, the development of this routine was a logical next step in helping teachers as they ensured that students acquired knowledge, understanding, and use of critical concepts.

Indeed, the two routines, Concept Mastery and Concept Anchoring, share common components. The most important of these is that key characteristics of a new concept are identified and highlighted by the teacher and students working together. With the Concept Anchoring Routine, however, students learn about a new concept by building on characteristics shared by the New Concept and an already Known Concept. Usually, the Known Concept is something with which they are familiar in their daily lives. In other words, through the use of this routine, students are building on their background knowledge of a Known Concept to understand a new and challenging concept through the use of an analogy. As such, this routine brings students’ prior knowledge and life experiences to the forefront when they are learning critical concepts.

Moreover, this routine contributes to a series of instructional practices that support a taxonomic hierarchy of learning that is reflected in subject-area learning demands. This routine supports students as they acquire understandings of a single critical concept, and these understandings may be applied to more complex and higher order thinking demands. This hierarchy of supports for thinking begins with facts and concepts, supports the manipulation of information, and finally leads to the use and generalization of important ideas and concepts.

My thoughts about Content Enhancement Instruction

As with the Concept Mastery Routine, the development and research on the Concept Anchoring Routine reinforced my commitment to the key principles that became the foundation for all the Content Enhancement Routines. Among these are that the teacher and students must be partners in learning and that learning must be as interactive and co-constructive as possible, given the large numbers of students in content classes. I also became very aware of the importance of focusing on critical information and concepts that would be used again and again. Furthermore, the wide range of students’ abilities, interests, and needs in general education classes verified the notion that innovative instruction was needed to help all students succeed.

Teacher Feedback on this Product

Many insights about teaching and learning came from working with the teachers who participated in developing and researching the Concept Anchoring Routing. One insight was that many teachers have preferred ways of thinking. Some teachers found the development of analogies to be easy and intuitive. As a result, they developed many Concept Anchoring Tables quickly and used them enthusiastically. Others found the development of good analogies more difficult.

Another great insight and understanding came from group discussions with the teachers, which were a big part of our development process. That insight was that, as teachers, we all have preferred ways of learning and explaining things. As teachers shared their ease or struggles with developing good concept analogies, they, as a group, came to the understanding that students also had preferred ways of learning. Another light bulb moment! The next group conclusion was that if they, as teachers, learned in different ways, they owed it to their students to teach in different ways. What a great moment to share with teachers!

Contact Information

Please contact me through Edge Enterprises, Inc. (877-767-1487).

Concept Comparison Routine: Instructor’s manual

Concept Comparison Routine: Instructor’s manual