Additional information

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

|---|---|

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Includes | 2 CD Set |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

|---|---|

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Includes | 2 CD Set |

The Beginner-Level Professional Development CD Program For Strategic Tutoring

Study 1

Overview

Strategic Tutoring is a specific type of tutoring that has been validated as effective in helping students be successful. Study 1 focused on the effects of a software program that was designed to teach tutors the basic skills associated with Strategic Tutoring. Twenty-four tutors and twenty-four high school students with learning disabilities (LD) participated. The tutors were randomly selected into an experimental or a control group. Likewise, the students were randomly selected into an experimental or control group. Each tutor was then matched with a student. The experimental tutors worked through the Beginner-Level software program; the control tutors did not. Two experimental designs were employed simultaneously during this study. The primary design was a multiple-probe across-tutors design (Horner & Baer, 1978), a variation of the multiple-baseline design. A pretest-posttest control-group design (Campbell & Stanley, 1963) was also used to compare the knowledge, think-aloud, and strategy-use scores of students of tutors in the experimental group and students of tutors in the control group to each other.

Results

When they were observed while tutoring a student, the tutors in the experimental group implemented an average of 15.5% of the Strategic Tutoring components during baseline. Then they worked through the CD program, and they completed an average of 94% of the instructional components and segments within the software program. After they completed the instruction and began working with students, they completed an average of 51.1% of the Strategic Tutoring components. The

tutors in the control group implemented an average of 22.1% of the Strategic Tutoring components during the baseline portion of the study and 20% of the components during the post-intervention portion of the study as they tutored students.

The mean baseline score was used as a covariate in an analysis comparing the mean scores earned after training by tutors in both groups. The criterion for significance for this ANCOVA test was set at 0.05. The results of this analysis revealed a significant difference between the mean post-intervention scores of the experimental and control group tutors [F(1, 24), = 78.3, p < .001, η2 = .986 (a very large effect)].

In addition, a t-test indicated that there was a significant difference between the mean baseline and post-intervention scores of the tutors participating in the Strategic Tutoring group [t (12) = 14.147, p < .001]. A t-test indicated that there was no significant difference between the mean baseline and post-intervention scores of the tutors participating in the control group [t (12) = 1.45, p = .174]. A Cohen’s d effect size was calculated at 5.1 (r = .93). This is a very large effect size.

On a written test of student strategy knowledge, the average score of experimental students was 25.9% on the pretest and 88.9% on the posttest. The average score of control students was 25.2% on the pretest and 28.2% on the posttest. An ANCOVA revealed a significant difference between the posttest scores of the experimental and control students [F(1, 24) = 33.4, p < .001, η2 = .915 (a large effect)] in favor of the experimental students who had participated in Strategic Tutoring.

When the students were asked to apply a strategy to an academic task, the average percentage score of experimental students was 10.8% on the pretest and 75.1% on the posttest. The mean percentage score of students in the control group was 9.2% on the pretest and 10.2% on the posttest. An ANCOVA revealed a significant difference between the posttest scores of the experimental and control groups of students on this measure [F(1, 24) = 34.3, p < .001, η2 = .951 (a very large effect)], in favor of the students who had received Strategic Tutoring.

When the students were asked to explain what they were doing while they completed the academic task, prior to the intervention, students in the experimental group explained an average of 7.5% of the steps and substeps of an appropriate strategy for completing the task. Following the intervention, these students explained an average of 59.2% of the steps and substeps. Prior to the intervention, students in the control group explained an average of 11.7 % of the steps and substeps. Following the intervention, control students explained an average of 14.2% of the steps and substeps. An ANCOVA revealed a significant difference between the posttest scores of the experimental and control student groups [F(1, 24) = 29.1, p < .001, η2 = .948 (a very large effect)], in favor of the students who had received Strategic Tutoring.

When they were asked to rate their satisfaction with the software program, the Strategic Tutors provided ratings of mostly “6” and “7’’ with an occasional “5” on a seven-point Likert-type scale. The mean rating for all items across all participants was 6.2. When the students were asked to rate the instruction they received from the Strategic Tutors, most of the experimental students provided ratings of “4,” “5,” and “6;” two students provided ratings of “1” and “2.” The mean rating for all items across all experimental students was 5.1.

Study 2

Overview

Study 2 was conducted following Study 1 and after the Beginner Level CD was revised. For this study, 24 adult tutors (teachers, paraprofessionals, and volunteers) participated: 12 were randomly assigned to the experimental group and 12 to the control group. Experimental group tutors worked through the Beginner CD; the control group tutors did not. In addition, 24 students were randomly selected into the experimental or control group and then matched to a tutor. A pretest-posttest control-group design was used for both tutor groups and student groups.

Results

Tutors in the experimental group completed an average of 92% of the instructional components and segments in the CD program.

When the tutors took a written test about tutoring, tutors in the experimental and control groups correctly answered an average of 2.3% and 3% of questions on the pretest, and 75.3% and 3.7% of the questions on the posttest, respectively. A t-test indicated that there was a significant difference between the average pretest and posttest knowledge scores of the tutors participating in the experimental group [t (11) = 22.6, p < .001]. No such difference was found for the control group [t (11) = 1.48, p = .166]. An ANCOVA revealed a significant difference between the knowledge test scores of the two groups [F(1, 24) = 6.517, p < .001], in favor of the experimental group. The value of the eta-squared statistic was .784, a large effect (Cohen, 1988).

When the tutors were observed while tutoring a student, tutors in the experimental group implemented an average of 20.8% of the Strategic Tutoring components prior to CD training and an average of 79% of the Strategic Tutoring components after training. The tutors in the control group implemented an average of 22.2% of the Strategic Tutoring components during the pretest portion of the study and 23.7% of the Strategic Tutoring components during the post-intervention portion of the study. A t-test indicated that there was a significant difference between the average pre- and post-intervention implementation scores of the tutors participating in the experimental group [t (11) = 37.6, p < .001]. No such difference was found for the control group [t (11) = 1.47, p = .171]. ANCOVA results indicated a significant difference between the post-intervention scores of the two groups [F(1, 24) = 27.52, p < .001], in favor of the experimental group. The value of the eta-squared statistic was .986, representing a very large effect (Cohen, 1988).

When the students took a written test about what to do as they approached an academic task, the average score for students in the experimental group on the pretest was 19.3% and on the posttest was 89.7%. The average score for students in the control group was 21.1% on the pretest and 23.8% on the posttest. ANCOVA results revealed a significant difference between the posttest scores of the experimental and control students [F (1, 24) = 10.88, p < .01], in favor of the experimental group. The value of the eta-squared statistic was .915, a large effect (Cohen, 1988).

When the students completed an academic task, the experimental students’ average percentage score was 17% on the pretest and 66.7% on the posttest. The mean percentage score of students in the control group was 17.8% on the pretest and 21.6% on the posttest. ANCOVA results revealed a significant difference between the posttest scores of the experimental and control groups of students on this measure [F(1, 24) = 36.1, p < .001], in favor of the experimental group. The value of the eta-squared statistic was .951, a very large effect (Cohen, 1988).

When the students were asked to explain what they were doing as they completed the academic task, prior to the intervention, experimental students explained an average of 14.8 % of steps and substeps of the targeted strategy. Following the intervention, students in the experimental group explained an average of 52.7% of the steps and substeps. Prior to the intervention, students in the control group explained an average of 12.1 % of steps and substeps. Following the intervention, control students explained an average of 13.3% of the steps and substeps. ANCOVA results revealed a significant difference between the posttest scores of the experimental and control groups of students [F(1, 24) = 37.2, p < .001], in favor of the experimental group. The value of the eta-squared statistic was .948, a very large effect (Cohen, 1988).

When the experimental tutors rated the CD program on a seven-point scale, their mean overall rating was 5.93. When the experimental students were asked to rate their satisfaction with Strategic Tutoring, most of the students provided ratings of “4,” “5,” and “6.” Three students provided ratings of “1” and “2.” In all three cases, they admitted to preferring more traditional tutoring because they were able to get answers to questions faster (i.e., their “traditional” tutors gave them the answers instead of requiring the students to derive their own answers). The mean overall rating for the experimental students was 5.1.

Conclusions

In both Studies 1 and 2, the Beginner Professional Development Program for Strategic Tutoring produced changes in tutor behavior such that tutors were using significantly more components of Strategic Tutoring after instruction than before instruction. In addition, they knew more about what a tutor is supposed to do in a tutoring session than the control-group tutors. Their students performed significantly better on an academic task and knew more about how to attack an academic task than the students of traditional tutors. Because the final level of performance of the experimental tutors was not as high as hoped for, another CD was designed to provide tutors with advanced skills related to Strategic Tutoring. The study that was conducted on this Advanced Professional Development Program is presented below.

The Advanced-Level Professional Development CD Program For Strategic Tutoring

Studies 1 and 2

Overview

Once the initial version of the Advanced-Level Strategic Tutoring CD-ROM (ALST) was developed, a formal pilot test (Study 1) was conducted with four tutors and eight students with LD. Each tutor worked with two students. All students were identified as having learning disabilities by their district and were receiving special education services for at least one class period per day. Two experimental designs were employed simultaneously during this study. The primary design was a multiple-probe across-tutors design, a variation of the multiple-baseline design. This design was replicated two times to determine the effects of the CD training on tutors’ implementation of Strategic Tutoring. A pretest-posttest design was used to compare the pretest and posttest scores of student participants.

After a pilot test was conducted with a few tutors, the field test involved a total of 28 tutors. All participating tutors in the field test completed the Beginner-Level Strategic Tutoring CD. Then fourteen tutors were randomly assigned to the experimental group, and 14 were assigned to the control group. Two tutors subsequently dropped out of the control group, leaving twelve in that group. In addition, 28 students had been randomly assigned to the control or experimental group and they were matched with a tutor in their assigned group. When the two tutors dropped out of the study, their assigned students no longer participated. Experimental tutors completed the Advanced-Level CD. Control tutors did not. Since all the tutors completed the Beginner CD, the purpose of this study was to determine what additional value the Advanced-Level CD provided to tutors. Each of the tutors worked with one student with learning disabilities (LD). A pretest-posttest control-group design was employed for both tutors and students.

Results

Tutors in the field test completed an average of 96% of the instructional components in the Advanced-Level software program for Strategic Tutoring.

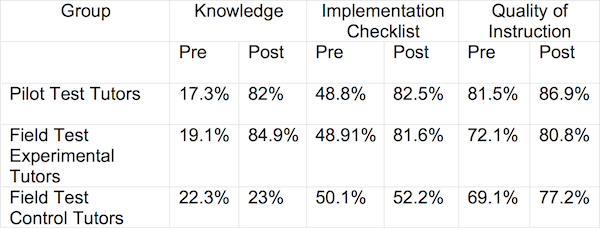

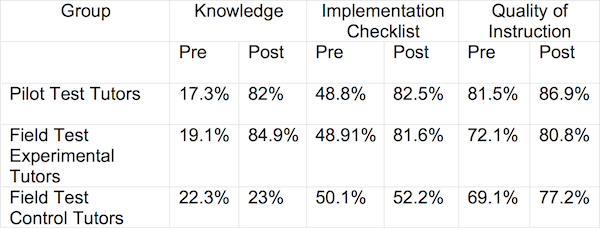

All the tutors completed a written knowledge test before and after all instruction. Mean scores on the Knowledge Test for pilot and field test tutors are summarized in the two columns at the left side of Table 1. For the field test, a t-test indicated that there was a significant difference between the average pretest and posttest knowledge scores of the tutors participating in the experimental group [t (13) = 27.8, p < .001]. No such difference was found for the control group [t (11) = .692, p = .504]. ANCOVA results indicated a significant difference between the knowledge scores of the two groups [F (1, 26) = 281.1, p < .001], in favor of the experimental group. The value of the eta-squared statistic was .957, representing a very large effect (Cohen, 1988).

Table 1: Mean Scores Earned by Tutors on the Knowledge, Implementation, and Quality Measures

All tutors were observed tutoring students before and after the experimental group tutors completed the Advanced-Level CD instruction. (All the tutors had completed the Beginner-level instruction before the pretest.) Mean implementation scores for participants in the pilot and field tests are summarized in the middle two columns of Table 1. With regard to the field test, a t-test indicated that there was a significant difference between the average pre- and post-intervention implementation scores of the tutors participating in the experimental group [t (13) = 12.68, p < .001]. No such pre- to post-intervention difference was found for the control group [t (11) = 1.64, p = .129]. ANCOVA results revealed a significant difference between the posttest implementation scores of the two groups [F (1, 26) = 85.5, p < .001]. The value of the eta-squared statistic was .881, representing a very large effect (Cohen, 1988).

Data on the quality of instruction provided by tutors who participated in the pilot test and field test are summarized in the last two columns at the far right side of Table 1. ANCOVA results for the field test revealed no significant difference between the post-intervention scores of the experimental and control groups (F (1, 26) = .871, p = .434) with regard to quality of instruction. The value of the eta-squared statistic was .080, representing a small effect (Cohen, 1988).

The students in both Study 1 and 2 took a written test of their knowledge of how to approach academic tasks. Their scores are summarized in the first two columns on the left side of Table 2. In the field test, posttest scores differed significantly from pretest scores for both the experimental and control groups [t (1) = 17.67, p < .001] and [t (11) = 7.14, p < .001], respectively. ANCOVA results revealed a significant difference between the posttest scores of the experimental and control groups [F (1, 26) = 7.01, p < .01], in favor of the experimental group. The value of the eta-squared statistic was .379, representing a large effect (Cohen, 1988).

The students also were given an academic task to complete. They were observed as they completed the task to determine whether they used strategic behaviors. Their strategy-use scores are summarized in the center two columns of Table 2. Results of t-tests indicated a significant difference between the pretest and posttest scores for both the experimental and control groups [t (13) = 16.04, p < .001] and [t (11) = 9.54, p < .001, respectively]. ANCOVA results revealed a significant difference between the posttest scores of the experimental and control groups of students [F (1,26) = 16.2, p < .01], in favor of the experimental group. The value of the eta-squared statistic was .585, representing a large effect (Cohen, 1988).

While the students were completing an academic task, they were asked to explain what they were thinking as they worked. Mean think-aloud scores for students who participated in both studies are included in the last two columns on the far right side of Table 2. Significant differences between the pretest and posttest scores were found for both the experimental and control group students [t (13) = 12.99, p < .001] and [t (11) = 4.47, p < .05, respectively]. ANCOVA results revealed a significant difference between the posttest scores of the experimental and control groups of students on this think-aloud measure [F (1, 26) = 7.11, p < .01], in favor of the experimental group. The value of the eta-squared statistic was .382, representing a large effect (Cohen, 1988).

Table 2: Mean Scores Earned by Students on the Knowledge, Strategy-Use, and Think Aloud Measures

Tutors in the experimental group who used the Advanced-level CD were asked to rate their satisfaction with the professional development program. They provided ratings of mostly “6” and “7’’ with an occasional “5” or “4” rating. The mean overall tutor rating was 6.2.

Conclusions

The pilot and field test results of these

studies replicate the results of the studies on the beginner-level professional development program for Strategic Tutoring. That is, after using the beginner-level CD, the experimental and control group tutors performed about 50% of the components of Strategic Tutoring (as shown in the pretest results). When the experimental group used the advanced-level professional development program for Strategic Tutoring in addition to the beginner-level program, they were able to perform more than 80% of the components of Strategic Tutoring. Thus, use of the Advanced-level CD in addition to the Beginner-level CD is critical to the proper use of Strategic Tutoring by tutors. Additionally, the student strategy-use results after tutors use the Beginner- and Advanced-level CDs are much improved over the student results after tutors only use the Beginner-level CD (90% versus 67%).

Reference

Lancaster, P. (2005). Effects of an e-learning professional development program for beginning Strategic Tutoring skills: SBIR Progress Report for Grant # 5R44HD45146-4. Washington, D.C.: The National Institute of Health.

Lancaster, P. (2006). Effects of an e-learning professional development program for advanced Strategic Tutoring skills: SBIR Progress Report for Grant # 5R44HD45146-4. Washington, D.C.: The National Institute of Health.

Paula E. Lancaster, Ph.D.

Affliations

My Background and Interests

For as long as I can remember, I was involved in the disability field in some capacity. First, as a family member, then as a young person volunteering, I was involved with Very Special Arts, Easter Seals, and the Special Olympics. Later, when I decided to major in special education, I continued my volunteer work and became interested in learning disabilities. Today, I teach graduate courses on learning disabilities at Grand Valley State University, continue with research and development activities through Edge Enterprises, and feel blessed to have found a career path where I can honestly say that if we hit the lottery tomorrow, I would continue to do this work as a volunteer. I’m still most interested in adolescent and young-adult issues and continue to work with local organizations in an effort to improve after-school programs for secondary students. My son, JD, learned his first strategy this year, and my daughter, Ellie, has two under her belt. They are currently a huge interest of mine!

The Story Behind the Strategic Tutoring Professional Development CDs

As a doctoral student, I had completed Strategic Tutoring training with Dr. Mike Hock and observed tutoring sessions for one of his research projects. I was very impressed with the care with which Strategic Tutoring was developed and then researched. Later, after I graduated, I was thrilled to have the opportunity to work on a project involving Strategic Tutoring. I believe Jean Schumaker suggested that we write a grant focusing on creating computerized professional development programs to accompany the excellent materials that Drs. Hock, Schumaker, and Deshler had developed. Clearly, Strategic Tutoring is a powerful intervention, but implementing it requires some knowledge and skills. Tutors must participate in professional development experiences to become competent Strategic Tutors. Based on what I have observed in the past, the people who are tutoring in schools or tutoring centers (i.e., volunteers, paraprofessionals, college students, parents) rarely receive any instruction for what they are expected to do. Creating a computerized program to provide this instruction to tutors seemed like a potential solution to a vexing problem. We have had a tremendous amount of support from Drs. Hock, Schumaker, and Deshler on this project and are grateful for their insights.

Two CD programs have been developed for tutors. The Beginner-Level CD program is based largely on the contents of the Strategic Tutoring manual and additional materials provided by Mike Hock, while the Advanced-Level CD program is based on effective staff development literature and materials Mike added as he continued to work with Strategic Tutors. Development of both programs followed the same process. In both cases, scripts were written, reviewed by the original authors, and sent back for revisions. While the scripts were being reviewed, video clips of Strategic Tutoring sessions were shot and edited. When the scripts were finalized, the program was built and pilot-tested with twelve tutors and their students. We were able to learn and gather a considerable amount of qualitative and quantitative data, all of which helped us make decisions regarding revisions in the CD programs. Once revisions were made, we completed a field test with 24 tutors and their students. Following the field test, the program was carefully edited by the authors and Jackie Shafer. At this time, we decided to replace some of the video clips in an effort to make them more concise. While very little dialogue was changed substantially, pauses and rough transitions were removed. During the field test, we did notice that many tutors were still missing a couple of important steps within the Strategic Tutoring process. For the descriptions of those steps, we made the narration and dialogue in the videoclips more overt and added an extra practice activity.

Once the CDs for tutors had been field tested and revised, a CD was created for directors of tutoring centers following the same development and testing process. This allows schools and other organizations to train their director as well as their tutors. Thus, each part of each of the Strategic Tutoring CDs has been carefully created and revised in an effort to provide the most effective instruction possible.

My Thoughts About Strategic Tutoring

I view Strategic Tutoring as an extremely powerful instructional approach. I’ve had the good fortune of seeing the positive results it affords students and tutors alike. People who do the work of tutoring seem to be hungry for professional development or any information they can find that will make them better. I encourage anyone who works in one-on-one or small-group instructional situations to take a close look at Strategic Tutoring. Dr. Mike Hock has continued his work in this area and has looked at various ways to make the model responsive to various academic needs including a focus on literacy skills.

Teacher and Student Feedback on this Product

I have no doubt that Strategic Tutoring is the most powerful tutoring approach available for students, but rarely do we see discussion of the effects on tutors. Through my work with community organizations that support during- and after-school tutoring, I’ve noticed that people who commit to tutoring whether for pay or as volunteers do so out of a desire to help students in need. I’ve heard from many tutors and the leaders of organizations that support these programs that adopting Strategic Tutoring has not only helped their students but it has empowered their tutors to feel like they are having a much greater impact on the children and young adults with whom they work.

My Contact Information

Email: lancastp@gvsu.edu

Work Phone: 616-485-4935

BUILD Strategy: Instructor’s Manual

BUILD Strategy: Instructor’s Manual