Additional information

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 50 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 2001 |

| Requirements |

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 50 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 2001 |

| Requirements |

Overview

The LINCing Routine is a set of procedures teachers use to teach students the LINCS Vocabulary Strategy. Students use the strategy to learn the meaning of a new word. The effects of teaching the LINCS Vocabulary Strategy were compared to the effects of teaching the Word Mapping Strategy in this study. The Word Mapping Strategy is a strategy students use to predict the meaning of new words. The study included a total of 230 ninth graders in nine intact general education English classes. Students with disabilities (SWDs) and without disabilities (NSWDs) were enrolled in each of the classes. Three classes participated in each of three groups: the group receiving instruction in the LINCS Vocabulary (VL) Strategy (n = 6 SWDs, 73 NSWDs), the group receiving instruction in the Word Mapping (WM) Strategy (n= 10 SWDs, 69 NSWDs) , and a comparison test-only [TO]) group (n = 8 SWDS, 64 NSWDs). Classes were randomly selected into the two experimental groups. The third group of classes served as a normative comparison. A pretest-posttest control-group design was combined with a pretest-posttest comparison-group design.

Results

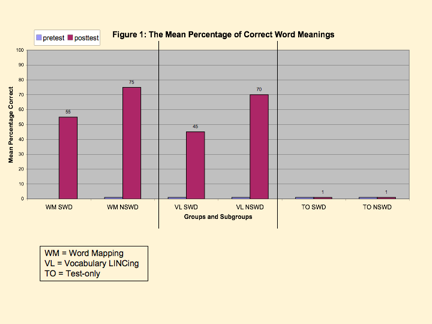

Figure 1 displays the mean percentage of 20 words that students in both experimental groups (i.e., the VL an/ WM groups) learned during the strategy instruction as determined by a written test that required students to write the meaning of the words. The mean scores of VL students are depicted with the bars in the center of the figure. With regard to changes from pretest to posttest for the VL group, the three-way interaction of time x subgroup x group was found to be significant, Wilks’ Λ = .964, F(2,224) = 4.138, p = .017, partial η2 = .036 (a small effect size). When the file was split on subgroup, the time x group interaction was significant for the SWDs, F(2,21) = 12.90, p < .001, partial η2 = .563 (a large effect size), and for the NSWDs, F(2,203) = 367.388, p < .001, partial η2 = .780 (also a large effect size). The paired-sample t-tests revealed that significant differences were found between the pretest and posttest scores for the SWDs in the VL group, t(5) = -5.391, p = .003, d = 1.074 (a large effect size), and for the NSWDs in the VL group, t(72) = -26.879, p< .001, d = .089 (a medium effect size). No differences were found for the TO subgroups.

No differences were found between the posttest scores of the VL and WM groups on this measure. However, large significant differences were found between the posttest scores of the VL subgroups and the TO subgroups [SWDs: F(1,20) = 12.589, p <.01, partial η2 = .386 (a moderate effect size); NSWDs: F(1,202) = 543.479, p <.001, partial η2 = .730 (a large effect size).

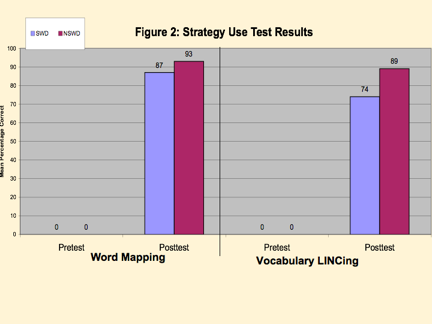

Figure 2 displays the mean percentage of points students earned on a test of strategy use, with the mean scores for VL students on the right side of the figure. Students in the VL group took a test requiring use of the LINCS Vocabulary Strategy; students in the WM group took a test requiring use of the Word Mapping Strategy. With regard to the VL group, a significant difference was found between the pretest and posttest scores, Wilks’ Λ = .262, F(1,77) = 217.184, p < .001, partial η2= .738 (a large effect size). There were no differences between the SWDs and the NSWDs in learning the LINCS Vocabulary Strategy.

Conclusions

Students in ninth-grade general education classes were able to learn the LINCS Vocabulary Strategy and the meaning of words taught during strategy instruction. The effect sizes in each case were large. There were no differences in performance between the students with and without disabilities.

Reference for this study*

Harris, M. L., Schumaker, J. B., & Deshler, D. D. (in preparation). The effects of strategic morphological analysis instruction on the vocabulary performance of secondary students with and without disabilities. Available through Edge Enterprises, Inc. or call Edge for updated publication information.

*This research study won the Researcher of the Year Award from the Council for Learning Disabilities in 2008.

|

Edwin (Ed) S. Ellis, Ph.D. Affliations

My Background and Interests During the late 1970s, due to my service volunteer experiences developing a pretrial diversion program for delinquent adolescents and working in a adolescent drug rehabilitation program, paired with my experience as a teacher of students with LD, I became the education coordinator for one of the Child Service Demonstration Centers (CSDC), which were federally funded programs charged with developing and validating interventions for students with LD. Our particular CSDC program focused on developing interventions for adolescents with LD who had been adjudicated (convicted). Of the many CSDCs that were funded, only a few focused on services for adolescents, and fewer still actually did anything to validate their effectiveness. One of these was a CSDC directed by Don Deshler, a new Assistant Professor at KU, and another one was directed by Naomi Zigmond at the University of Pittsburgh. Those of us concerned with the validation of our programs would meet at conferences to share what we were doing and our data. These were exciting times for all of us, and especially for me because I was collaborating with some brilliant people, and we were all trying to figure out what to do, how to do it, and how well it worked. Most of the CSDCs, however, failed to validate their interventions, so subsequent federal support shifted to funding five research institutes where learning disabilities could be addressed in a systematic, empirical manner, and interventions could be scientifically validated. Dick Shieffelbush and Ed Meyen were awarded one of these institute grants, and thus the Institute for Research in Learning Disabilities (KU-IRLD) was born. Don Deshler, who was the Coordinator for the KU-IRLD recruited many of us who had been collaborating with him within the CSDCs to come to KU for doctoral studies and to work at the KU-IRLD (now known as the KU-CRL). That’s how I landed in Kansas, and that’s how I became a part of an effort to change education that continues today. The Story Behind the LINCS Vocabulary Routine What I learned while doing these “guest teacher” presentations was that most of the typical learners could readily acquire the LINCS Strategy, but students who were struggling to learn tended to need more intensive and extensive instruction in it for them to know how to perform it well enough to use it independently. I also learned that even when I did not provide the intensive strategy instruction to my students, they still benefited greatly when general education teachers embedded their subject-area instruction with activities that involved creating LINCS devices for the new vocabulary. From this knowledge sprang the LINCing Routine. My Thoughts about Content Enhancement Instruction Teacher Feedback on the LINCS Vocabulary Routine My Contact Information |

||

Word Identification Strategy: Instructor’s Manual

Word Identification Strategy: Instructor’s Manual