Additional information

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Other Materials Needed | Student practice materials: Practicing the Storage Strategies and Lexicons |

| Requirements |

Learning—and remembering—the meaning of new vocabulary words is not always easy! Students buy often have to take weekly tests covering the meaning of 20 or more vocabulary words. If they want to go to college, they need to know the meaning of hundreds of words to do well on college entrance exams. This is a daunting task for many students!

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Other Materials Needed | Student practice materials: Practicing the Storage Strategies and Lexicons |

| Requirements |

Overview

The LINCS Vocabulary Strategy is a strategy students use to learn the meaning of a new word. The effects of teaching the LINCS Vocabulary Strategy were compared to the effects of teaching the Word Mapping Strategy in this study. The Word Mapping Strategy is a strategy students use to predict the meaning of new words. The study included a total of 230 ninth graders in nine intact general education English classes. Students with disabilities (SWDs) and without disabilities (NSWDs) were enrolled in all of the classes. Three classes participated in each of three groups: the group receiving instruction in the LINCS Vocabulary (VL) Strategy (n = 6 SWDs, 73 NSWDs), the group receiving instruction in the Word Mapping (WM) Strategy (n= 10 SWDs, 69 NSWDs), and a comparison test-only [TO]) group (n = 8 SWDS, 64 NSWDs). Classes were randomly selected into the two experimental groups. The third group of classes served as a normative comparison. A pretest-posttest control-group design was combined with a pretest-posttest comparison-group design.

Results

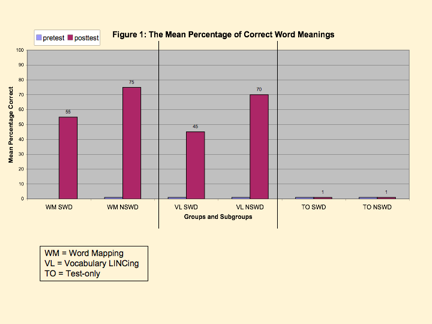

Figure 1 displays the mean percentage of 20 words that students in both experimental groups (i.e., the VL and WM groups) learned during the strategy instruction as determined by a written test that required students to write the meaning of the words. The bars in the center of the figure show the mean percentage scores earned by the VL group before and after instruction in the strategy. With regard to changes from pretest to posttest for the VL group (the group that learned the LINCS Strategy), the three-way interaction of time x subgroup x group was found to be significant, Wilks’ Λ = .964, F(2,224) = 4.138, p = .017, partial η2 = .036 (a small effect size). When the file was split on subgroup, the time x group interaction was significant for the SWDs, F(2,21) = 12.90, p < .001, partial η2 = .563 (a large effect size), and for the NSWDs, F(2,203) = 367.388, p < .001, partial η2 = .780 (also a large effect size). The paired-sample t-tests revealed that significant differences were found between the pretest and posttest scores for the SWDs in the VL group, t(5) = -5.391, p = .003, d = 1.074 (a large effect size), and for the NSWDs in the VL group, t(72) = -26.879, p< .001, d = .089 (a medium effect size). No differences were found for the TO subgroups.

No differences were found between the posttest scores of the WM and VL groups on this measure. However, large significant differences were found between the posttest scores of the VL subgroups and the TO subgroups [SWDs: F(1,20) = 12.589, p <.01, partial η2 = .386 (a moderate effect size); NSWDs: F(1,202) = 543.479, p <.001, partial η2 = .730 (a large effect size).

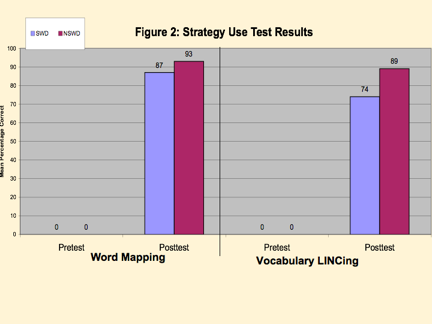

Figure 2 displays the mean percentage of points students earned on a test of strategy use. Students in the VL group took a test requiring use of the LINCS Vocabulary Strategy; students in the WM group took a test requiring use of the Word Mapping Strategy. With regard to the VL group whose mean scores are depicted in the bars on the right side of Figure 2, a significant difference was found between the pretest and posttest scores, Wilks’ Λ = .262, F(1,77) = 217.184, p < .001, partial η2= .738 (a large effect size). There were no differences between the SWDs and the NSWDs in learning the LINCS Vocabulary Strategy.

Conclusions

Students in ninth-grade general education classes were able to learn the LINCS Vocabulary Strategy and the meaning of words taught during strategy instruction at a high level of performance. The effect sizes in each case were large. There were no differences in performance between the students with and without disabilities.

Reference for this study*

Harris, M. L., Schumaker, J. B., & Deshler, D. D. (in preparation). The effects of strategic morphological analysis instruction on the vocabulary performance of secondary students with and without disabilities. Available through Edge Enterprises, Inc. or call Edge for updated publication information.

*This research study won the Researcher of the Year Award from the Council for Learning Disabilities in 2008.

Edwin (Ed) S. Ellis, Ph.D.

Affliations

My Background and Interests

Although I didn’t realize it at the time, my interest in learning and teaching began way back in 1965 at age 15. My youngest brother had been diagnosed with learning disabilities, and with both parents working 80+ hours a week, many of the responsibilities for his treatment fell on my shoulders. This was back when perceptual motor training to establish brain hemisphere dominance to cure LD was in vogue. I spent countless hours doing “angels in the snow” types of activities with him and trying to help him learn to read and write, although I was somewhat clueless about how to do it. His and my own emotional experiences led me to pursue college studies in the area of psychology, and becoming a teacher never crossed my mind. I accidentally fell into special education when an opportunity presented itself with a tuition grant to pursue a master’s degree in special education/learning disabilities. I didn’t have anything else to do, and it seemed like a way to extend my interest in psychology in a practical way. Only when I had my own classroom and became very invested in understanding my students did I realize that I was one of those people who was “born to teach”… and born to observe and think about learning. I’ve been hooked ever since!

During the late 1970s, due to my service volunteer experiences developing a pretrial diversion program for delinquent adolescents and working in a adolescent drug rehabilitation program, paired with my experience as a teacher of students with LD, I became the education coordinator for one of the Child Service Demonstration Centers (CSDC), which were federally funded programs charged with developing and validating interventions for students with LD. Our particular CSDC program focused on developing interventions for adolescents with LD who had been adjudicated (convicted). Of the many CSDCs that were funded, only a few focused on services for adolescents, and fewer still actually did anything to validate their effectiveness. One of these was a CSDC directed by Don Deshler, a new Assistant Professor at KU, and another one was directed by Naomi Zigmond at the University of Pittsburgh. Those of us concerned with the validation of our programs would meet at conferences to share what we were doing and our data. These were exciting times for all of us, and especially for me because I was collaborating with some brilliant people, and we were all trying to figure out what to do, how to do it, and how well it worked. Most of the CSDCs, however, failed to validate their interventions, so subsequent federal support shifted to funding five research institutes where learning disabilities could be addressed in a systematic, empirical manner, and interventions could be scientifically validated.

Dick Shieffelbush and Ed Meyen were awarded one of these institute grants, and thus the Institute for Research in Learning Disabilities (KU-IRLD) was born. Don Deshler, who was the Coordinator for the KU-IRLD recruited many of us who had been collaborating with him within the CSDCs to come to KU for doctoral studies and to work at the KU-IRLD (now known as the KU-CRL). That’s how I landed in Kansas, and that’s how I became a part of an effort to change education that continues today.

The Story Behind the LINCS Vocabulary Strategy

Like many Resource Room teachers of students with LD, I worked with a range of different general education teachers to monitor my students’ academic performance in subject-areas courses (e.g., to learn about up-coming assignments, what tasks my students were struggling with, their successes). One of the most common requirements of these courses was learning vocabulary – LOTS of it. I was aware of the rich amount of research about use of mnemonic devices to help students learn new information, and in particular, I was aware of the work of Drs. Margo Mastropieri and Tom Scruggs on providing students with visual mnemonic devices, developed by teachers, to teach vocabulary. As a teacher, my primary goal was to teach my students strategies that led to independence, but much of the previous mnemonic strategy research was about teacher-constructed mnemonic devices. I wanted my students to learn to develop and use mnemonic devices independently. I started to develop a set of instructional methods to teach students to do just this, and the LINCS Strategy was born. It enables students to use a variety of memory tools to help them remember the meaning of new words.

When developing the LINCS Strategy intervention, I realized that teaching students to construct effective memory devices for learning vocabulary was only half the problem – the other half was teaching them how to make decisions about when to use the LINCS Strategy and when not to bother. Thus, I found that students also needed to learn how to evaluate the complexity of new terms and how to determine which terms justify the development of LINCS devices.

My thoughts about Learning Strategy Instruction and the LINCS Strategy

Most teachers of struggling students know that they tend to use very ineffective strategies for learning and are also very resistant to learning more effective and efficient strategies, so part of the challenge of teaching learning strategies is motivating students to learn and use them. Some learning strategies are a lot easier to learn than others; likewise, some provide more immediate and obvious “pay-off” than others. Thus, another reason I developed the LINCS Strategy was I needed a strategy that was relatively easy to learn and also one that students could immediately experience the benefits of using it in “real world” (general education) classes. Thus, many teachers select the LINCS Strategy as one of the first they teach students who are new to learning strategy instruction. When students experience the immediate and very real benefits, they tend to more readily “buy-in” to the concept of learning new strategies and are more amenable to learning those that are more difficult to acquire but also critical to use.

Teacher or Student Feedback on the LINCS Vocabulary Strategy

The feedback from teachers and students about the LINCS Vocabulary Strategy has been overwhelmingly positive. I literally have several drawers full of LINCS samples that students have sent me over the years, and I continue to receive a steady stream of them. It’s a pretty cool feeling. About 95% of the teachers with whom I’ve shared LINCS love the strategy. Nevertheless, what has consumed me are the 5% who don’t. What I’ve come to realize about them is that their discontent is a professional development (PD) issue, not a strategy issue. I’ve learned that these teachers view LINCS as a superficial gimmick that’s not really teaching vocabulary. They view LINCS this way because one part of the LINCS Strategy focuses on the use of key-word mnemonic devices. It’s this feature that the 5% seem to view as non-authentic learning. Their concerns about use of mnemonic devices tends to overshadow the other really powerful, yet very subtle, features of the LINCS Strategy, so they miss them. For example, when using the strategy, students analyze new terms to determine which ones should be targeted for extensive study. They analyze definitions to determine critical elements, and they transform these often stilted, mechanical definitions into their own language. Further, they engage in various brain-based elaboration learning strategies as they systematically study the terms, and they learn to monitor their progress and degree of test-readiness. During the process of creating LINCS devices, students have to re-visit and think about a new term’s definition many times, and in many different ways. Thus, the strategy involves a number of cognitive tools that prepare them for academic success in a variety of ways.

Perhaps the most important feature these teachers fail to perceive is the dramatic impact the LINCS Strategy has on students. The obvious impact is students’ almost immediate increased performance on tests. The not-so-obvious, but ultimately much more important impact is the effect that the LINCS Strategy has on students’ sense of empowerment. There’s been a common theme among comments from a great many teachers and parents, as well as a few students… that is, they report that students often experience a transformation from being a victim of a hard test to an attacker of a hard test. It’s feedback about this attack-attitude transformation that thrills me the most about the impact of the LINCS Strategy.

So why is it a PD issue? When the 5% of teachers fail to see the more subtle, yet very powerful features of the LINCS Strategy, it’s because I failed to sufficiently teach them about those features. In other words, it was a teaching problem, not a strategy problem. Because I failed as a professional developer, these teachers never attempted to teach LINCS because they didn’t see the value in it. When they don’t teach LINCS, they then don’t have the opportunity to experience, first hand, its real impact. As a professional developer, I’ve come to realize that teachers will perceive the more subtle features of LINCS if you teach them about these features.

My Contact Information

Please contact me at edwinellis1@gmail.com or at (205) 394-5512.

Main Idea Strategy: Improving Reading Comprehension Through Inferential Thinking...

Main Idea Strategy: Improving Reading Comprehension Through Inferential Thinking...