Additional information

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

|---|---|

| Year Printed | 2013 |

| Other Materials Needed | The Framing Routine |

| Requirements |

This Interactive Frames flash drive can be used along with the Framing Routine. It contains 22 digital Frames (11 color, 11 blackline) as well as samples of how they can be used. Teachers or students can use a keyboard to type information directly into the text boxes on the Frames. Teachers can email the Frames to students, so students can use them when completing assignments outside of the classroom, and students can submit their work to teachers electronically. Completed Frames can also be saved electronically in a folder containing other related unit information. The Frames can be displayed using digital projectors and filled in during discussions and class activities.

$18.00

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

|---|---|

| Year Printed | 2013 |

| Other Materials Needed | The Framing Routine |

| Requirements |

Study 1

Overview

In this study, 32 high-achievers, 32 normal achievers, and 16 students with learning disabilities (LD) participated, along with their two secondary social studies teachers. The study compared the students’ performance on oral tests after their teachers presented information with a Frame and the Framing Routine versus having students participate in guided notetaking on an outline of the information. It also compared three subgroups of students’ scores on the tests: high achievers, normal achievers, and students with learning disabilities. The oral tests required the students to explain relationships among specified terms and to elaborate on concepts. Specifically, they were prompted to summarize important ideas about a given topic, to relate or apply ideas related to the topic, and to think about an idea in a new way (What if…?). A reversal design was used. During Phases 1 and 3, the guided-notes method was used by the teachers. During Phases 2 and 4, the Framing Routine was used.

Results

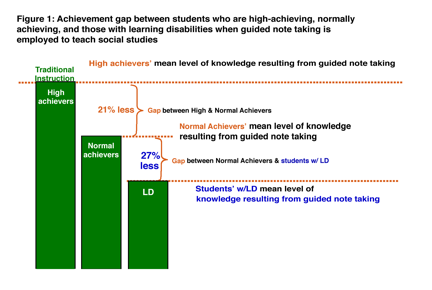

Figure 1 summarizes the results from the guided note-taking phases. High-achieving students earned scores that were, on average, 21 percentage points higher than scores of the normal achievers. Further, normal achievers earned scores that were, on average, 27 percentage points higher than the scores of students with LD.

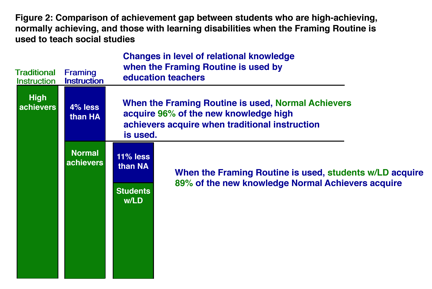

Figure 2 summarizes the results from the Framing Routine phases. The high achievers earned scores that were 4 percentage points higher than the scores of normal achievers, and the normal achievers earned scores that were 11 percentage points higher than the scores of the students with LD, on average. Thus, when the routine was used, the students with LD acquired about 89% of the information acquired by the normal achievers.

Conclusions

These results show that the use of the Framing Routine can be beneficial to all three groups of students in inclusive classes: high achievers, normal achievers, and students with LD. It is a method that can be used to close the gap between what students with LD traditionally learn and what their peers learn.

Reference

Ellis, E. S. (2007). The effect of Frames with semantic prompts on closing the achievement gap in students’ knowledge of history. Retrieved on June 16, 2009 from www.MakesSenseStrategies.com.

Study 2

Overview

The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of teaching students to use the Frame (the graphic organizer used with the Framing Routine) to guide their performance on a writing assignment. A total of 52 eighth graders participated. Twenty of the students were normally achieving students, and 32 were students with learning disabilities (LD). The students with LD were randomly assigned to two groups: an experimental group and a control group. The experimental group received 30 minutes of instruction per day for 10 days in the use of the Frame to guide their writing of expository essays in their language arts classes. The control students received traditional writing instruction in their classes. The number of words written by the students was counted in essays written by the students before and after the experimental students received the instruction. The normally achieving group of 20 students also wrote essays to serve as a normative comparison group. They received only traditional writing instruction.

Results

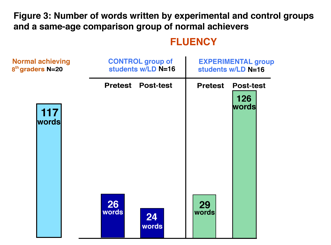

The results are shown in Figure 3. The normally achieving students produced essays that were an average of 117 words in length. Students with LD in the control group produced essays that were an average of 26 words long on the pretest and 24 words long on the posttest. Students with LD in the experimental group produced essays that were an average of 29 words long on the pretest and 126 words long on the posttest.

Conclusions

Instruction in general education language arts classes in how to use the Frame to guide the writing of expository essays yielded results for students with LD that were not only comparable to but exceeded the results for normal achievers who had received traditional instruction with regard to the number of words written.

Reference

Ellis, E. S., & Feldman, K. (2007). The effect of Frames on the writing fluency of eighth-grade students with learning disabilities. Retrieved on June 18, 2009 from www.MakesSenseStrategies.com

Edwin (Ed) S. Ellis, Ph.D.

Affliations

My Background and Interests

Although I didn’t realize it at the time, my interest in learning and teaching began way back in 1965 at age 15. My youngest brother had been diagnosed with learning disabilities, and with both parents working 80+ hours a week, many of the responsibilities for his treatment fell on my shoulders. This was back when perceptual motor training to establish brain hemisphere dominance to cure LD was in vogue. I spent countless hours doing “angels in the snow” types of activities with him and trying to help him learn to read and write, although I was somewhat clueless about how to do it. His and my own emotional experiences led me to pursue college studies in the area of psychology, and becoming a teacher never crossed my mind. I accidentally fell into special education when an opportunity presented itself with a tuition grant to pursue a master’s degree in special education/learning disabilities. I didn’t have anything else to do, and it seemed like a way to extend my interest in psychology in a practical way. Only when I had my own classroom and became very invested in understanding my students did I realize that I was one of those people who was “born to teach”… and born to observe and think about learning. I’ve been hooked ever since!

During the late 1970s, due to my service volunteer experiences developing a pretrial diversion program for delinquent adolescents and working in an adolescent drug rehabilitation program, paired with my experience as a teacher of students with LD, I became the education coordinator for one of the Child Service Demonstration Centers (CSDC), which were federally funded programs charged with developing and validating interventions for students with LD. Our particular CSDC program focused on developing interventions for adolescents with LD who had been adjudicated (convicted). Of the many CSDCs that were funded, only a few focused on services for adolescents, and fewer still actually did anything to validate their effectiveness. One of these was a CSDC directed by Don Deshler, a new Assistant Professor at KU, and another one was directed by Naomi Zigmond at the University of Pittsburgh. Those of us concerned with the validation of our programs would meet at conferences to share what we were doing and our data. These were exciting times for all of us, and especially for me because I was collaborating with some brilliant people, and we were all trying to figure out what to do, how to do it, and how well it worked. Most of the CSDCs, however, failed to validate their interventions, so subsequent federal support shifted to funding five research institutes where learning disabilities could be addressed in a systematic, empirical manner, and interventions could be scientifically validated.

Dick Shieffelbush and Ed Meyen were awarded one of these institute grants, and thus the Institute for Research in Learning Disabilities (KU-IRLD) was born. Don Deshler, who was the Coordinator for the KU-IRLD recruited many of us who had been collaborating with him within the CSDCs to come to KU for doctoral studies and to work at the KU-IRLD (now known as the KU-CRL). That’s how I landed in Kansas, and that’s how I became a part of an effort to change education that continues today.

The Story Behind the Framing Routine

The roots of the Framing Routine derived from my experiences during my doctoral studies. I was one of the high school teachers of students with LD who were conducting studies sponsored by the University of Kansas Institute for Research on Learning Disabilities (KU-IRLD) to validate instruction for specific learning strategies. One of these studies involved teaching and validating a writing strategy, the Theme Writing Strategy (known as “TOWER”), designed by Jean Schumaker. Use of the strategy included a prewriting activity that involved recording and prioritizing ideas on a hierarchical graphic organizer. This graphic organizer provided the foundation upon which the “Frame” subsequently evolved. At the time, however, it was solely viewed as a writing tool.

A few years later, Jan Bulgren developed one of the first KU-IRLD interventions that focused on strategic approaches to content instruction. It involved use of a graphic organizer she designed as a tool for teaching abstract concepts (this intervention eventually evolved into the Concept Mastery Routine). Although I found her work very interesting, my interest at the time was in teaching learning strategies, not teaching content.

Two catalysts subsequently changed my whole way of thinking about graphic organizers. First, while co-authoring the curriculum for CEC’s Academy for Effective Instruction, Anita Archer shared her research with me on using graphic organizers depicting different ways of organizing information to teach content-area subjects. The simplicity of the techniques and their impact as tools to help students learn content-area information was an epiphany for me. At about the same time, Mike Pressley, a cognitive psychology researcher, and I were frequently co-presenters at conferences; many late night discussions and his articles profoundly affected my thinking about strategic instruction and its theoretical and empirical basis. In particular, his work helped me recognize the importance of an embedded curriculum associated with teaching information processing and fostering use of cognitive elaboration strategies when using graphic organizers in the classroom. Of the hundreds of papers Mike published, Elaborating to Learn and Learning to Elaborate (CITE) was one of the most influential for me. I began to revisit Jan Bulgren’s work and the “TOWER” graphic organizer with a whole new perspective.

My thinking about graphic organizers was also strongly influenced by my on-going experiences as a college professor, doing volunteer work, and conducting studies in secondary classrooms. A considerable amount of this work involved experimenting with various graphic organizers in a range of teaching and learning contexts. All of this eventually led to developing ways to use graphic organizers as “Think ahead” techniques for use at the beginning of a lesson to activate knowledge and stimulate interest, “Think During” techniques for use during the lesson to maximize student elaboration of the to-be-learned material, and “Think-back” techniques for use at the end of a lesson to facilitate reflective review of the material. It also included a range of ways to use graphic organizers to teach reading, writing, and learning strategies. Over the years, I experimented with many graphic organizers, including a range of modifications of the “TOWER” graphic organizer and contexts for using it. The graphic organizer eventually evolved into the “Frame” that is used in conjunction with the Framing Routine. One of my goals for the Framing Routine instructor’s manual was to show teachers how the same basic graphic organizer can be used for a range of different purposes; thus, instructions for using the Frame along with Think-Ahead, Think-During, and Think-Back instructional tactics appear in the manual.

My thoughts about Content Enhancement Instruction and the Framing Routine

When I read Lenz and Bulgren’s first piece introducing the concept of Content Enhancement (CE), I was intrigued, mostly by what seemed to be a new dimension that these researchers were integrating into strategic instruction. I didn’t fully appreciate the elegant simplicity underlying the notion of enhancing content because the article was what one might characterize as a “heavy read,” steeped in theoretical notions and complex analysis of related research. The more I worked with CE materials, however, the more I’ve come to realize what a simple, yet incredibly powerful notion CE represents. Two CE principles are paramount: (a) increasing the learnability of subject-matter is preferable to dumbing it down, and (b) extraordinary teaching that impacts all students should be implemented before taking extraordinary measures such as providing individual accommodations. CE puts the role of accommodations in its proper place –they should be used as a last resort, rather than the first option. Historically, education has been steeped in the notion that failure to learn is the student’s fault (e.g., the result of a learning disability, poor motivation, etc.). CE redefines failure to learn by adhering to the radical notion that failure to learn is first and foremost a teaching problem, not a student problem.

One of the positive trends resulting from the No Child Left Behind legislation has been the focus on scientifically validated interventions, that is those educational practices that have been empirically validated using scientific experimental research methodologies. What is often missing from research reports about the effectiveness of new techniques is information regarding their social validity. In other words, the new practice or procedure may be validated as effective because student achievement improves when it is used, but that does not mean it will be used in the “real world” of everyday classrooms. The new technique may not have social validity because it may be too difficult to learn to use, too time consuming to apply, require too much advance planning, students may not like it, and/or it may require teachers to make radical adjustments in their own teaching philosophy to accommodate its use. Fortunately, the Framing Routine seems to have clearly met the “reality” test. I’ve received a lot of emails from teachers and parents expressing appreciation. It’s difficult to be modest and proud at the same time, but I admit it. I’m very proud of the impact this routine has had. It continues to touch the lives of a great many students.

Teacher and Student Feedback on the Framing Routine

I am very optimistic about the extent to which teachers at all levels of schooling are now using graphic organizers, and in particular, the Frame. It is one of those tools that can be integrated across subject areas so that students can learn to use it in very flexible ways to be more successful in a variety of contexts. For example, in one middle school, I observed a social studies teacher using the Frame during a guided note-taking activity and another social studies teacher using it during a “jig-saw” cooperative-learning text-chapter reading activity. In another wing of the building, 8th-grade students were using the Frame to record observations during experiments. At the same time, 8th-grade language arts teachers were using it in full-inclusion classes. The more sophisticated writers were using it to plan their persuasive essays, while at the same time, students with developmental disabilities were using the same tool while learning to write simple paragraphs. Teachers and students have sent me thousands of examples of how they have used the Frame. Applications range from kindergarten classes, where students have drawn and colored pictures depicting a story sequence to medical school, where students have used the Frame to organize information in preparation for their Medical Board Examinations.

Below are samples of unsolicited comments I’ve received about the Framing Routine.

“This stuff has totally changed my way of thinking about teaching. We used Frames for everything — taking notes when reading, organizing ideas when writing, planning projects, organizing activities, brainstorming ideas — I mean everything. It’s really helped my students learn how to organize their thinking. The Frame is one of the best, most versatile teaching tools I’ve ever seen. My kids are always focusing on the main ideas and the big picture.”

Theresa Farmer, 2001-02 Ala Teacher of the Year

Fifth grade teacher

Oak Mountain Intermediate School

Birmingham, AL

“I’m a special education teacher who works with a sixth-grade middle-school team of teachers in a total- inclusion situation. We’ve used the Frame graphic organizer extensively, especially as a tool for facilitating note taking and writing. We were amazed at how well it helped our students. One child with mental retardation was able to write an entire page about his favorite teacher. In the past, about all he could do was string a couple of sentences together — at best.

We keep copies of the Frame in a box, and students just go up and get one anytime they want. They used to ask permission if they could use one, but now they just go get one anytime. It’s become kind of automatic for them — especially when they are doing group work or cooperative-learning activities.”

Tuwanna McGee

Westlawn Middle School

Tuscaloosa, AL

“I took a copy of the Frame down to a local printer and had several poster-sized versions made up and then laminated them. We use the laminated posters for group work. Students note their ideas using water-based markers. To re-use the posters, we just wipe them off with a damp paper towel. The Frames are a great way to structure and focus student’s responses during group activities.”

Betty Hudgins

5th grade teacher

Scarsdale, NY

“The Frame helps my students to see connections in their learning, and they seem to retain more subject content. Using the Frame has opened the door of opportunity for all students to comprehend what they are learning. It’s not just the trivial facts that are being emphasized when using frame, but the big ideas that are presented allow the diverse class of today to interpret the lessons. Students love to keep frames in their notebooks as study guides and references. Making a Frame is easy and fun.”

Frances Weatherly, Ph.D.

5th grade social studies teacher

Verner Elementary

Tuscaloosa, AL

“The Frame is the most fundamental graphic organizer I share with teachers and graduate students. The structure of the graphic organizer prompts teachers and students to organize their thinking about any content area topic in terms of main ideas and critical details, the most common text structure students encounter in secondary content-area classes. As teachers mediate student use of the Frame, they, in effect, become “cognitive coaches” teaching students how to independently organize factual information during reading, lecture/discussions, or before writing.”

Kevin Feldman, Ph.D.

Director of Reading & Early Intervention

Sonoma County Schools, CA

My Contact Information

Please contact me at edwinellis1@gmail.com or at (205) 394-5512.

Fundamentals in the Sentence Writing Strategy: Instructor’s Manual

Fundamentals in the Sentence Writing Strategy: Instructor’s Manual