Additional information

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 50 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 1997 |

| Requirements |

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 50 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 1997 |

| Requirements |

Overview

The Clarifying Routine is used by teachers to teach students about an abstract idea or concept through exploration of its critical features, examples and non-examples associate with it, and its connections to background knowledge. This study examined the effects of using the Clarifying Routine on the learning of 53 students. The study took place in three general education classes, with each class from a different school. The 6th-grade class (Class A) was composed of students attending a middle school located in a high socioeconomic metropolitan area. The second group of students (Class B) attended a “looping class” for 4th- and 5th-grade students in an elementary school located in a middle socioeconomic area of a small town. The third group of students (Class C) attended a “looping class” for 4th- and 5th-grade students in an elementary school located in a low socioeconomic (inner-city) metropolitan area.

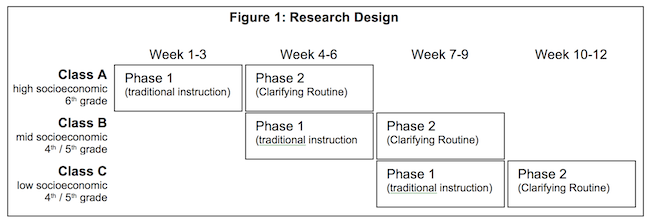

Each class experienced two instructional phases. Phase 1 involved traditional instruction; Phase 2 featured use of the Clarifying Routine by the teacher. The study employed a staggered pretest/posttest design where the point in time in which the Clarifying Routine was implemented served as the primary control for the study (see Figure 1). Thus, when Class A completed Phase 1 instruction, Class B began Phase 1 instruction. When Class B completed Phase 1 instruction, Class C began Phase 1 instruction. In all phases, students took a multiple-choice exam over the content of the lessons. During each phase, three pre- and post-instruction measures were taken.

Results

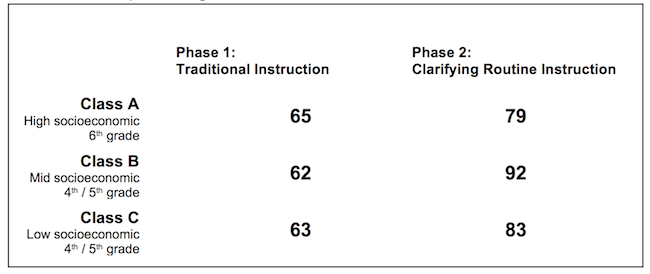

Table 1 shows the results of the study. Markedly similar results were found regardless of socioeconomic status. When the Clarifying Routine was employed to teach abstract concepts, the mean number of questions answered correctly by students attending the high-socioeconomic-status school increased by an average of 14 points over traditional instruction. The performance of students in the middle-socioeconomic-status school increased by an average of 30 points, and the performance of students in the low- socioeconomic-status school increased by an average of 20 points.

Table 1: Mean percentage of answers correct on tests

Conclusions

In short, these data show that students answered substantially more test questions correctly when the Clarifying Routine was used to teach abstract concepts that when traditional instructional methods were employed. The routine improved performance across socioeconomic levels and grades four through six.

Reference

Ellis, E. S., Raines, C., Farmer, T., & Tyree, A. (in prep). Effectiveness of a concept clarifying routine in upper-elementary and middle-school general education classes.

Edwin (Ed) S. Ellis, Ph.D.

Affliations

My Background and Interests

Although I didn’t realize it at the time, my interest in learning and teaching began way back in 1965 at age 15. My youngest brother had been diagnosed with learning disabilities, and with both parents working 80+ hours a week, many of the responsibilities for his treatment fell on my shoulders. This was back when perceptual motor training to establish brain hemisphere dominance to cure LD was in vogue. I spent countless hours doing “angels in the snow” types of activities with him and trying to help him learn to read and write, although I was somewhat clueless about how to do it. His and my own emotional experiences led me to pursue college studies in the area of psychology, and becoming a teacher never crossed my mind. I accidentally fell into special education when an opportunity presented itself with a tuition grant to pursue a master’s degree in special education/learning disabilities. I didn’t have anything else to do, and it seemed like a way to extend my interest in psychology in a practical way. Only when I had my own classroom and became very invested in understanding my students did I realize that I was one of those people who was “born to teach”… and born to observe and think about learning. I’ve been hooked ever since!

During the late 1970s, due to my service volunteer experiences developing a pretrial diversion program for delinquent adolescents and working in a adolescent drug rehabilitation program, paired with my experience as a teacher of students with LD, I became the education coordinator for one of the Child Service Demonstration Centers (CSDC), which were federally funded programs charged with developing and validating interventions for students with LD. Our particular CSDC program focused on developing interventions for adolescents with LD who had been adjudicated (convicted). Of the many CSDCs that were funded, only a few focused on services for adolescents, and fewer still actually did anything to validate their effectiveness. One of these was a CSDC directed by Don Deshler, a new Assistant Professor at KU, and another CSDC was directed by Naomi Zigmond at the University of Pittsburgh. Those of us concerned with the validation of our programs would meet at conferences to share what we were doing and our data. These were exciting times for all of us, and especially for me because I was collaborating with some brilliant people, and we were all trying to figure out what to do, how to do it, and how well it worked. Most of the CSDCs, however, failed to validate their interventions, so subsequent federal support shifted to funding five research institutes where learning disabilities could be addressed in a systematic, empirical manner, and interventions could be scientifically validated.

Dick Shieffelbush and Ed Meyen were awarded one of these institute grants, and thus the Institute for Research in Learning Disabilities (KU-IRLD) was born. Don Deshler, who was the Coordinator for the KU-IRLD recruited many of us who had been collaborating with him within the CSDCs to come to KU for doctoral studies and to work at the KU-IRLD (now known as the KU-CRL). That’s how I landed in Kansas, and that’s how I became a part of an effort to change education that continues today.

The Story Behind the Clarifying Routine

Mike Pressley, Jan Bulgren, and the KISS Principle (Keep It Simple Sailor) inspired the development of the Clarifying Routine. The graphic organizer used in conjunction with this instructional routine was originally called a “metacab.” [META meaning knowledge of and CAB, short for vocabulary]. The metacab was designed as both a tool for teaching vocabulary and as a tool for teaching about the information structure of vocabulary to intermediate and middle-school students. It has subsequently become a tool also used by high school and college students.

The Clarifying Routine was developed with three criteria in mind. The first was to develop a device (the Clarifying Table) that contained embedded semantic prompts designed to cue the teacher or student to employ a select set of information-processing tactics that research had shown to be highly effective when teaching vocabulary. The second was to develop a tool that focused on meaningful understanding of abstract concepts. The third criterion was simplicity. Like the LINCS Strategy and LINCing Routine, I wanted a device that would be easy for teachers and students to learn to use and would lead to experiences that would make teachers want to learn more of the Content Enhancement Routines.

My Thoughts about Content Enhancement Instruction

When I read Lenz and Bulgren’s first piece introducing the concept of Content Enhancement (CE), I was intrigued, mostly by what seemed to be a new dimension that the KU-CRL was integrating into SIM. I didn’t fully appreciate the elegant simplicity underlying the notion of enhancing content because the article was what one might characterize as a “heavy read,” steeped in theoretical notions and complex analysis of related research. The more I worked with CE materials, however, the more I’ve come to realize what a simple, yet incredibly powerful notion CE represents. Two CE principles are paramount: (a) increasing the learnability of subject-matter is preferable to dumbing it down, and (b) extraordinary teaching that impacts all students should be implemented before taking extraordinary measures such as providing individual accommodations. CE puts the role of accommodations in its proper place –they should be used as a last resort, rather than as the first option. Historically, education has been steeped in the notion that failure to learn is the student’s fault (e.g., the result of a learning disability, poor motivation, etc.). CE redefines failure to learn by adhering to the radical notion that failure to learn is first and foremost a teaching problem, not a student problem.

Teacher and Student Feedback on the Clarifying Routine

One of the positive trends resulting from the No Child Left Behind legislation has been the focus on scientifically validated interventions, that is, those educational practices that have been empirically validated using scientific experimental research methodologies. What is often missing from research reports about the effectiveness of new techniques is information regarding their social validity. In other words, the new practice or procedure may be validated as effective because student achievement improves when it is used, but that doesn’t mean it will be used in the “real world” of everyday classrooms. The new technique may not have social validity because it may be too difficult to learn to use, too time consuming to apply, require too much advance planning, students may not like it, and/or it may require teachers to make radical adjustments in their own teaching philosophy to accommodate its use. Fortunately, the Clarifying Routine seems to have clearly met the “reality” test. I’ve received a lot of emails from teachers and parents expressing appreciation. It’s difficult to be modest and proud at the same time, but I admit it. I’m very proud of the impact this routine has had. It continues to touch the lives of a great many students. Feedback from teachers and students about the Clarifying Routine has been that they want a lot more routines like it. Thus, the empirical and social validity of the Clarifying Routine really served as the catalyst for the development of an extensive range of similar tools, collectively known as the Makes Sense Strategies.

My Contact Information

Please contact me at edwinellis1@gmail.com or at (205) 394-5512.

Commas Strategies Digital Program for Students Flash Drive

Commas Strategies Digital Program for Students Flash Drive