Additional information

| Cover | Paperback |

|---|---|

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 2012 |

$15.00

| Cover | Paperback |

|---|---|

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 2012 |

Overview

The Main Idea Strategy is a strategy to improve the performance of students with learning disabilities and other students who perform poorly on reading comprehension tasks requiring them to comprehend inferential main ideas. The Main Idea Strategy consists of five steps that are aimed at deriving the main idea from the key details. Teachers teach the strategy to students following an instructional sequence divided into four parts.

Highly qualified secondary teachers with an average of approximately 18 years of teaching experience provided the strategy instruction in the research study. Twenty-two students from the teachers’ middle- and high-school classes participated, based on low performance in class and on state tests and IEP goals related to reading comprehension. Teachers taught the strategy in their classes over approximately five months within one school year. The researcher provided follow-up visits to the teachers to trouble-shoot and enhance implementation. Three measures were used: a highlighting measure, where students highlighted essential details in a passage; a main-idea paraphrasing measure, where students expressed the main idea of a paragraph in their own words in writing; and a comprehension measure where students wrote answers to comprehension questions about a passage.

Results

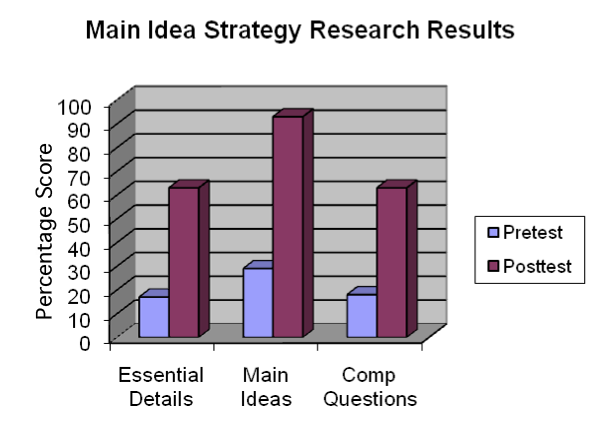

Students showed pretest to posttest score gains, considerable improvement through on-going curriculum-based measurement, and changes in state test performance. Mean student percentage scores increased substantially from the pretest to the posttest, from approximately 15% to 60% on the highlighting essential details measure, from approximately 28% to 90% on the main-idea paraphrasing measure, and from approximately 16% to 60% on the comprehension questions measure. Using on-going curriculum-based assessment, students steadily enhanced their performance on all measures throughout the study, even as the readability of the passages increased from about the third-grade level at the beginning of the instruction to nearly the ninth-grade level toward the end of the study. In addition, based on teacher reports, 100% of the participating middle-school students passed the state reading test, whereas only approximately 63% had passed the test previous to the study.

Teachers and students provided social validation for the strategy instruction. Mean teacher responses to 7-point Likert-type scale questionnaire items ranged from 6.0 to 7.0, based on questions about how well the strategy instruction fit teaching responsibilities and beliefs about teaching, to the ease of implementation and student performance. Teachers also commented that they observed students transferring or generalizing the use of the strategy to other reading tasks without prompting. Students responded to 7-point Likert-type scale questions with mean ratings ranging from 5.17 to 5.53, addressing questions about ease of understanding the strategy to questions about how much they thought the strategy helped them become a better reader. One student commented “The strategy helped me improve my science grade a lot! Without even knowing that I was using it when I was taking notes and stuff then I was!”

Conclusions

Student understanding of inferential main ideas impacts many areas of academic performance, including measures of Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) used by public school districts for accountability under No Child Left Behind regulations. Whether this strategy is introduced in a regular classroom, resource room, tutoring program, or home school setting, it has the potential to improve the performance of students who struggle to understand inferential main ideas in their reading.

References

Boudah, D. J. (2008). The Main Idea Strategy: Improving reading comprehension through inferential thinking (Teacher Instructional Manual) (2nd ed.). Lulu Publishing: Lulu.com.

Boudah, D. J., & Harris, N. (2006, April). Collaborative research and evaluation of inferential main idea strategy. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, CA.

Daniel J. (Dan) Boudah, Ph.D

Affliations

My Background and Interests

I’ve been East. I’ve been West. I’ve been to the Midwest. I’ve also lived in Texas and now in the South. I think that living and teaching in many places around the country has enriched my perspective on people and education. Having been a general education teacher first and then a special education teacher has also shaped the way I look at the lives of teachers and students. My continuing opportunities to spend time in classrooms, conducting demonstration lessons and providing instructional coaching, as well as assisting school and district leaders, continues to enhance the way I think and what I do.

Now, I’m not a person who always wanted to be an educator. I thought I was going to be a rich and influential businessman. That’s the direction I started off as an undergraduate, but I had a change of heart, and I decided that investing in people, rather than dollars, was more important to me. I switched majors, completed my B.S. at the University of Vermont and started teaching English/Language Arts in a small, rural district in Vermont. After a few years, I became quite interested in the challenges faced by the students who were “mainstreamed” into my classes in the mid 1980s. As a result, I enrolled in and completed the Consulting Teacher/Learning Specialist master’s degree program at the University of Vermont. After that, my new bride and I decided to pack up the wagon, like the Beverly Hillbillies, and head west to California. There, I became a special education teacher, facilitated inclusive instruction for students with learning and behavioral disabilities, and began conducting professional development for teachers.

While in California, I first met Don Deshler and Jean Schumaker at a conference. I had valued their work for some time, and eventually decided to head to the University of Kansas to study for my doctorate and work at the Institute for Research on Learning Disabilities, which expanded and was renamed the Center for Research on Learning. Since being transformed as a person and professional at Kansas, I have worked at a couple of different universities in Texas and North Carolina.

Based on my years as an educator, particularly my years in public schools, there are a number of critical incidents that stand out in my memory; one, in particular, dramatically shaped my approach to what I now do. When I was teaching in public schools in California, a group of well-meaning researchers from a prestigious university asked several colleagues and me to participate in a research study. They treated us well and politely asked us to try out certain materials with our academically diverse classes. They soon returned, with clipboards in hand, to watch and take copious notes while we taught and students worked. After several weeks, with handshakes and sincere “thank-yous,” the researchers were gone, and never heard from again.

Thus, as a result of that and several other critical incidents, coupled with invaluable opportunities in many different places, the goals of my continuing work are as follows: first, to be field-based; second, to be collaborative in nature; third, to treat teachers and students not as subjects and outsiders, but as participants and partners; fourth, to make sure my work is useful, realistic, and sustainable; and fifth, to improve the lives of teachers, students with disabilities and others at-risk for failure, particularly at the secondary level.

My continuing professional interests focus on the following areas: programs and services for low-performing students and students with disabilities, learning strategies and instructional strategies, the Content Literacy Continuum, dropout prevention, and systems change. I continue to enjoy opportunities to be engaged in professional development, curriculum design, program evaluation, grant and foundation proposal development, and system change activities with public and private schools, as well as public and private agencies to develop and support services to low-performing and at-risk students.

Pamela (my wife) and I, with our two incredibly wonderful children, live in North Carolina

The Story Behind the Main Idea Strategy

The Main Idea Strategy emerged from my experiences, first, as an English/Language Arts teacher. I became aware that many students in middle and high school could not understand what they read. Unfortunately, this is still true, and perhaps more importantly, many students have a particularly hard time finding main ideas when they have to “read between the lines” to infer the main ideas. This appears to be true for students with and without disabilities, and across different disciplines in which they have to read for meaning.

Therefore, given the context of student needs and demands, as well as the proven success of some existing learning strategy programs, the Main Idea Strategy was researched and developed based on several important points. First, previously developed strategies to enable low performing students to read and understand main ideas may be insufficient because they are often limited to finding literal, rather than inferential, main ideas. Second, most secondary school reading requires that students infer meaning from poorly organized and written textbooks. Third, high or even acceptable student performance on state reading tests depends on students’ success at determining inferential main ideas, affecting districts’ measures of Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) in conjunction with No Child Left Behind regulations.

Teacher and Student Feedback on the Main Idea Strategy

I trust that you will find success using the Main Idea Strategy, as have many teachers and students already. Perhaps this student has expressed the value of the strategy best: “The strategy helped me improve my science grade a lot! Without even knowing that I was using it, when I was taking notes and stuff, then I was!”

My Contact Information

Please contact me at dboudah@nc.rr.com or boudahd@ecu.edu. You can also reach me on facebook, at drdanboudah.com, or simply by phone at 919.308.8923.

Makes Sense Strategies Flash Drive

Makes Sense Strategies Flash Drive