Additional information

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 92 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 2006 |

$15.00

| Dimensions | 8.5 × 11 in |

|---|---|

| Cover | Paperback |

| Dimensions (W) | 8 1/2" |

| Dimensions (H) | 11" |

| Page Count | 92 |

| Publisher | Edge Enterprises, Inc. |

| Year Printed | 2006 |

Overview

The Focusing Together Program is used to teach students how to stay on task and be productive in their classrooms while following basic classroom rules. To test the effects of the instructional program, a study was conducted in eight classrooms with a total of 225 students in grades four and five. The classrooms were randomly selected into an experimental and a control group. The four teachers of the experimental classes taught their students the strategies associated with the Focusing Together Program and continued using the program with the students. The four teachers in the control classes did not use the Focusing Together Program.

Observers visited the eight classrooms regularly. They observed the off-task behaviors of five students in each classroom using an interval recording system, with intervals lasting 60 seconds long. Each group of five students included one high achiever, one average achiever, one low achiever, and two students with disabilities. The observations lasted 15 minutes each during a time when students were completing independent work. Six observations were completed in each classroom, with three observations occurring at the beginning and three at the end of the study. Example off-task behaviors included being out of one’s seat, looking around the room, talking, playing with objects, and not following the teacher’s directions.

Results

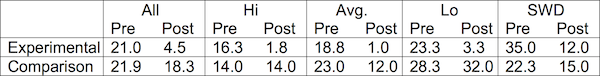

At the beginning of the study, the observers recorded a mean of 21 off-task intervals in the experimental classrooms and a mean of 22 off-task intervals in the control classrooms (within the total of 45 intervals). At the end of the study (after the experimental classes had Focusing Together instruction), the observers recorded a mean of 5 off-task intervals for the experimental students and 18 off-task intervals for the control students. All types of students in the experimental classrooms exhibited a decrease in the number of off-task intervals. See Table 1 for results for the subgroups of students.

When the teachers were asked to rate their satisfaction with their own class management skills and how well their students followed the rules and worked independently, the experimental teachers had a mean rating of 6.06, and the control teachers had a mean rating of 3.56 on a 7-point scale (with “7” equal to “completely satisfied”).

Moreover, when asked to report rule infractions for a two-week period at the beginning and end of the study, the experimental teachers reported a 72% reduction, while the control teachers’ report remained the same across the study period.

Conclusions

This study showed that students with reading and writing disabilities could learn to write essay answers in response to essay questions such that their content and organization improved. In addition their essay answers were comparable to the answers of students without disabilities.

Reference

Rademacher, J. A., Pemberton, J. B., & Cheever, G. L. (2006). Focusing together: Promoting self-management skills in the classroom. Lawrence: Edge Enterprises, Inc.

Joyce A. Rademacher, Ph.D.

Affliations

My Background and Interests

My interest in teaching began when I was in first grade. I loved “teaching school” during my elementary years and recruited younger children in the neighborhood to be my “students.” Thus, I knew exactly what I wanted to do when I enrolled at Texas Lutheran College in 1960: to become a teacher. I loved observing in the schools as part of my course requirements, and I was particularly interested in the students who struggled to learn. During my junior year, I transferred to the University of Houston to complete my degree because that institution began to offer an endorsement in special education. Since my graduation in 1964, I have gained knowledge and experience from a number of perspectives. Because I was a military wife, I experienced many moves. As a result, I had an opportunity to work in a variety of settings throughout the country. For example, I have taught students with mild mental retardation in self-contained classrooms and students with learning disabilities in a resource room. I have also worked as a special education consulting teacher and as an educational therapist in a hospital setting for adolescents with emotional/behavior disorders. In addition to my special education experiences, I was also a general education teacher for students in grades one, four, five, and six. Prior to completing my doctoral studies at the University of Kansas in 1993, I was an elementary school principal. I am currently a Professor of Special Education at Texas Woman’s University where I prepare teachers at the undergraduate and graduate levels to teach students with disabilities. I am also an active member of the Strategic Instruction Model Professional Development Network. My research interests focus on issues related to teacher preparation and on the research and development of instructional methods that can be used to teach students how to learn and be successful in inclusive settings.

The Story Behind the Focusing Together Program

My work over the past 30 years as a classroom teacher, an elementary school principal, and now as a university professor who prepares future teachers, has greatly influenced the research and development of the Focusing Together program. For example, during my earlier years as both a special or general education classroom teacher, I took pride in being an effective classroom manager. My principal often asked me to share my classroom rules and procedures with other teachers. She also commented on how self-directed my students appeared to be in their learning as a result of the management procedures I was using. Later, as an Educational Therapist in a hospital setting for adolescents with emotional/behavior disorders, I used the same set of rules to teach classroom survival skills in order for these students to be successful when they transitioned to their home schools. I developed lessons in which we talked about the rationale for each rule and its benefits, and then guided students through role-playing situations to help them practice following a particular rule. This approach appeared to be successful as students became confident in how to act in a particular situation in a way that prevented them from getting into trouble with their teachers and peers. Finally, when I was a school principal, I provided professional development to my teachers on how to design an effective rule-management system that included many of the procedures I had developed during my earlier work with the adolescents. Parents were informed of the rule-management program and were pleased with the rules that promoted respect, good work habits, and safety across all school settings. When I became a university professor, I learned that classroom management is high on the concern list for new teachers entering the profession. I then became eager to share with them the ideas that had been successful for me and others. At that point, I knew a research study to refine and test the procedures I had previously implemented with my students was absolutely necessary. The Focusing Together program is an outcome of that research.

My Thoughts about the Focusing Together Program

I view the Focusing Together program as a way to create a classroom learning community in which students and teachers work together to abide by a set of expectations that define respect, good work habits, and safety. During our research, my co-authors and I decided to use the term “expectations” instead of “rules” for four reasons. First, students may view rules as negative and punitive in nature, rather than as guidelines for teaching them how to learn and get along with others. Second, expectations are more closely associated with the notion of what one can do in order to be personally responsible for his or own behavior. Third, some schools have a set of prescribed rules that each classroom teacher is expected to enforce, making two sets of rules confusing. Finally, having a list of learning community expectations is more personal in nature and can be associated with, or compared to, the school rules if necessary.

Thus, the Focusing Together program helps students make decisions about their behavior that result in acceptance by peers and teachers. They learn how to maintain their personal power by making the right choices in situations rather than losing personal power by making the wrong choices. Making the right choices allows students to be positively regarded in inclusive classrooms, in the school, and in community settings.

The Focusing Together program helps teachers because they have the language that is understood by students to create a positive learning community. Teachers report that once students understand what is expected by all members of the class, they begin to help one another learn and get along during learning activities.

Teacher and Student Feedback on the Theme Writing Strategy Program

The Focusing Together program has been well received by both teachers and students. For example, co-teaching is a model in my state that is being implemented in a variety of settings. In this model, a general and special educator work as a team to plan and teach the class. Focusing Together has been a popular program for co-teachers because it sets high expectations for learning and working together. One general education co-teacher commented that the special educator had a great tool to help support special education students while simultaneously helping all learners in the class maintain their personal power. University students expressed appreciation on the clarity of instruction in setting up classroom expectations and knowing how to teach them and positively reinforce them. One fifth grader said “Thanks for teaching my class how to learn and work together. We all like having personal power!”

My Contact Information

Joyce Rademacher, Ph.D

Professor of Special Education

Department of Teacher Education

Texas Woman’s University

P.O. Box 425769

Denton, TX 76204-5769

Email: jrademacher@twu.edu

Work Phone: 940-898-2272

Following Instructions Together: Instructor’s Manual

Following Instructions Together: Instructor’s Manual